Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

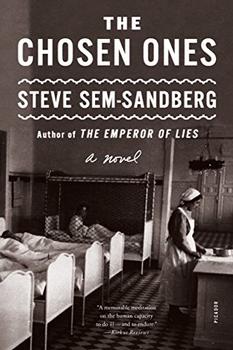

A Novel

by Steve Sem-Sandberg

Mr Pawlitschek's Money Rudolf Pawlitschek had this habit of boasting about his prowess as a huntsman, never mind that he had only one arm. Once, Mr Pawlitschek invited Adrian into his room next to the hallway and told him that he would be allowed to watch how one went about greasing a hunting rifle. The rifle hung on a hook above Mr Pawlitschek's bed. While he outlined some of his sporting feats, he took it down, laid it across his parted thighs and extracted a tin of gun grease and a cloth from the drawer in his bedside table. The cleaning started with Mr Pawlitschek ramming the muzzle into his left armpit and then rotating the gun by alternately tightening and relaxing his grip with what was left of the stump on his shoulder as he wiped it down using strong, even strokes with the cloth. It looked funny. His armpit kept releasing and catching the gun while his right hand rubbed and rubbed on the same spot. The effort made Mr Pawlitschek sweat copiously and, all the while, the sweat seemed to soften his sour, twisted face until a grimace almost like a smile was spreading across it. When Mr Pawlitschek had finished and put the cloth and the tin of grease back in the drawer, Adrian caught sight of a bundle of bank notes squashed in at the back. It became instantly fixed in his mind. Every morning, as he dragged himself to the school on Münnichplatz, his thoughts circled around the money and the image stayed with him all the hours he spent sitting on the seat Mr Bergen had exiled him to, right at the back of the classroom, where he was left to his own devices because Bergen persistently, patiently ignored Adrian and directed his questions to the other children. Adrian thought that he would count the money one day when Mr Pawlitschek wasn't at home. He wouldn't do anything else, only count the notes to find out how much the stash was worth. The right moment arrived sooner than he had dared to hope. When he came home from school one afternoon, the Haidingers and the Pawlitscheks (senior and junior) were out and the rifle had gone from its hook on the wall, so Adrian opened the drawer, removed the tin of gun grease and the cloth, then the notes, pulled off the rubber band and started counting with trembling fingers. Sixty Reichsmarks. In that moment a decision was made, but not by Adrian; as he explained later, instead his mind had been made up for him. Actually, it was more like an incontrovertible fact rather than any kind of choice because what to do next must be done for the simple reason that the money was in that drawer and this was the day when no one was in, except the cows and the rabbits. It took him only minutes to put the notes in his pocket, pack some clothes in his satchel and catch the tram towards Schwarzenbergplatz. Far fewer people were out strolling along the Inner Ring than on the afternoon when Adolf Hitler's cavalcade ploughed through the huge crowds, and soon Adrian was stopped by a policeman on his beat. In the thirties, school-age children were not usually drifting about on their own in central Wien. Besides, guardian or no guardian, this boy with his dark tinker's face and grass-stained pants, the only trousers Mrs Haidinger let him wear when he was at home and made to clean the rabbit hutches, didn't come across as a believable schoolchild. The officer, pretty certain that he had caught an experienced pick-pocket whose school satchel was nothing but camouflage, felt vindicated when he found the bundle of bank notes. Adrian was taken to the police station, the money was properly counted and he had to confess all. He was Adrian Dobrosch (not yet Ziegler!) and, yes, he had taken Mr Pawlitschek's savings, intending to keep half for himself to pay for food and somewhere to live, and give the rest to his mother for the rent. Tell me, who's your mother? the policeman asked with a cunning smirk, as if he reckoned he was about to catch an entire gang of thieves, but Adrian fell silent at that point.

Excerpted from The Chosen Ones by Steve Sem-Sandberg. Copyright © 2016 by Steve Sem-Sandberg. Excerpted by permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.