Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

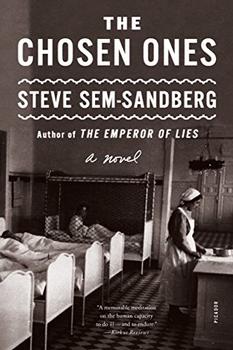

A Novel

by Steve Sem-SandbergI

Fostered Children

The Institution They brought him to Spiegelgrund for the first time in January 1941, on a cold, clear winter's morning when the pale light closest to the ground shimmered with frost. Near the top of the mountain that rose behind the pavilions, Adrian Ziegler remembers seeing the institution's church, its dome green with verdigris against a blue sky, an unreal blue like that of postcards or colour-printed posters. The car stopped just inside the hospital gate, in front of the buildings that housed the directorate and the administration. A nurse came to escort them, first to meet the elderly director, a grave, pale gentleman in a dark suit, who signed the documents, and then to a pavilion to the left of the main entrance, where a doctor was waiting to examine him. Another nurse was there as well and she shouted at him to undress at once and step onto the scales. Adrian would claim that he had no idea who the doctor was until much later. It was only then, when he finally saw the medical report and recognised the signature of Doctor Heinrich Gross, that he identified the Spiegelgrund doctor as the man who pursued him for the rest of his life, even long after he had been set free. But on this first day, the doctor is simply a frightening stranger in a white coat who forces his jaws apart as far as they will go, and then probes and squeezes the bones in his skull and spine with strong fingers. The examination lasts for an hour and the doctor uses instruments that Adrian has never seen before. The top of his head is measured using a kind of circular tool with a sharp point at the tip. He is told to sit on a tall seat made up of a loose board with flaps on either side and then Doctor Gross lowers another measuring thing to determine the distance between his eyes, and between each eye and his chin. Next, the doctor pulls on a pair of gloves, prods Adrian's testicles and pushes a finger up his anus. When the examination is done, the escort nurse comes to collect him. It is still early. They walk along a corridor where the white winter daylight bounces off the monotonous pattern of rhomboid floor tiles and it will often come back to him afterwards how the floors and walls in corridors and dormitories glowed with an unearthly luminosity as if alive in their own right, independent of the children who stayed there and somehow more substantial than they were. But, of course, the nurse has no patience with him. Stop staring and come along, we haven't got all day! They go outside through a door at the back of the building. Now, he has his first glimpse of the extent of the place that will be his home for several years, of its many pavilions lined up side by side, pale and shut-off in the long, frost-white shadow below the mountain. All the pavilions look the same, with barred windows and plain brick frontages broken by bays. The narrow tracks of a tramline apparently link the pavilions. From a little higher up, a small train comes along, three freight wagons pulled by a red and white locomotive. It looks like a toy train. He is to be housed in pavilion 9, in the third row to the left of the central path. The nurse pulls out a huge bunch of keys from her apron pocket and flicks through them with practised fingers until she has located the right one. The dormitory doors must be locked even though it is mid-morning. If there are any children behind the doors, they aren't making the slightest noise. The nurse leads the way to a store cupboard next to the washroom and hands him a towel and a piece of grey institutional soap. He has a bath and afterwards she inspects his fingernails and ears, then lets him have his clothes back. She gives him a pair of felt slippers to wear indoors and a short, grey woollen jacket, but he isn't allowed to put the jacket on even though the corridor is as cold as sin. She leads him to a tall white door with IV painted on it. At first, he thought the children behind that door were just sitting very still and holding their breath. Later, he thought maybe they were already dead but pretended to be alive for his sake. So he wouldn't lose heart straightaway.

Excerpted from The Chosen Ones by Steve Sem-Sandberg. Copyright © 2016 by Steve Sem-Sandberg. Excerpted by permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.