Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

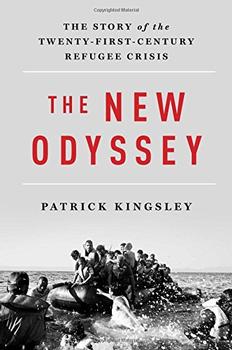

The Story of the Twenty-First Century Refugee Crisis

by Patrick Kingsley

There are obvious security concerns inherent in the passage of thousands of undocumented people to Greece. But short of ripping up the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, the only way of mitigating these concerns would have been, for the reasons outlined above, to provide legal, orderly entry to significant numbers of them. Such a move would have decreased the flow across the Aegean, and consequently could have made it easier to monitor and control who was entering Europe. But no one had the vision to think this far ahead. Instead, fear of social meltdown was used to excuse inertia – fear that became its own self-fulfilling prophecy.

In spring 2016, Europe finally found a strategy that, at the time of writing, had at least brought the numbers down. The EU promised to pay Turkey €6 billion, in exchange for their policing their borders better and readmitting all those landing in Greece. The flow fell. In the early weeks of the deal, mere hundreds came * Despite subsequent legislative changes in January 2016, the vast majority of Syrians still have no access to the legal labour market in Turkey.to the Greek islands, rather than the thousands who had landed in previous months. The isolationists claimed victory.

But in the medium to long term, they are likely to be disappointed. The deal may have collapsed by the time you read this, with Turkey threatening to reopen the floodgates if Turkish holidaymakers aren't given easier access to the EU. Meanwhile, maritime refugee flows continue between Libya and Italy, and people are still crossing the land border between Turkey and Bulgaria. These routes may prove even more popular once Syrians in Turkey realise that Greece is not the option it once was. And even if they don't, then all this will have come at great humanitarian and moral cost. Millions will now be stuck in the Middle East, in countries where – despite recent legislative changes – refugees do not in practice have the right to work, where Syrians cannot afford to feed their children, and where hundreds of thousands of those children are therefore forced into child labour. And all this will have been achieved by destroying the 1951 Refugee Convention – the document that was drawn up in the aftermath of the Holocaust to ensure that refugees would never again be turned away from the borders of the Western world.

Amid all this hand-wringing, many refugees nevertheless still continued to cross the sea – and many of them still drowned. Just to reach the boat in the first place, most of them had been on journeys that deserve to be considered a contemporary Odyssey. At a time when travel is for many easy and anodyne, their voyages through the Sahara, the Balkans or across the Mediterranean – on foot, in the holds of wooden fishing boats and on the backs of land cruisers – are almost as epic as those of classical heroes such as Aeneas and Odysseus. I'm wary of drawing too strong a link, but there are nevertheless obvious parallels. Just as both those ancient men fled a conflict in the Middle East and sailed across the Aegean, so too will many migrants today. Today's Sirens are the smugglers with their empty promises of safe passage; the violent border guard a contemporary Cyclops. Three millennia after their classical forebears created the founding myths of the European continent, today's voyagers are writing a new narrative that will influence Europe, for better or worse, for years to come.

This book is about who these voyagers are. It's about why they keep coming, and how they do it. It's about the smugglers who help them on their way, and the coastguards who rescue them at the other end. The volunteers that feed them, the hoteliers that house them and the border agents who try to keep them out. And the politicians who look the other way.

Based on interviews and encounters in seventeen countries across three continents, it tells the story of both the Mediterranean crossing and the crossing of what aid workers call Libya's second sea, the sea of the Sahara – and then the onwards march through Europe. It's reported from the hideouts of Berber smugglers and the ports of Sicily; from the railways of western Europe and the footpaths of the Balkans. Along the way, it's a critique of Europe's handling of the migration crisis and an argument for how it could be handled better. The crisis will be with us in some form for several years to come; in this book, I want to recount what happened in 2015, the year that it reached unprecedented proportions and what we can learn from it.

Excerpted from The New Odyssey by Patrick Kingsley. Copyright © 2017 by Patrick Kingsley. Excerpted by permission of Liveright / WW Norton. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.