Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Petrograd, Russia, 1917 - A World on the Edge

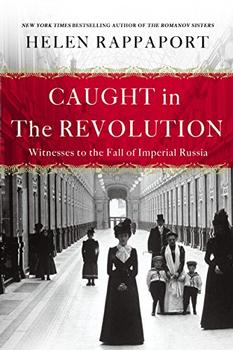

by Helen Rappaport

The unsinkable Thompson, from Topeka, Kansas, was a scrawny but feisty five feet four inches, familiar for his signature jodhpurs and flat cap, the Colt in his waistband and the camera he carried with him everywhere. He had tried eight times to get to the Western Front as a war photographer – each time being turned back by the military authorities, his film or cameras confiscated. He finally made it, filming at Mons, Verdun and the Somme, among many locations on the front line, and smuggling his film back to London or New York. He had headed to Russia in December 1916 with Harper, having been tipped off that 'they expect trouble here', and with an additional commission to shoot footage for Paramount.

Like many Americans in Russia for the first time, Thompson, Harper and Fleurot, as well as others who followed, had 'come breezing into Petrograd with that all-conquering, all-knowing American optimism'. But 'gradually the weather, the melancholy of the Russians, the seriousness of everything under the sun, would dampen their mood'. To get to Petrograd, Harper and Thompson had taken the alternative route into Russia then available: a boat across the Pacific to Japan and thence to Manchuria, where they picked up the Trans-Siberian railroad. They arrived complete with Thompson's bulky cameras and tripod and Harper's extensive and mostly unsuitable wardrobe, Thompson having noted with amusement that 'Florence Harper, on account of her extra baggage, had to buy six extra railroad tickets'. Arriving in Petrograd at 1.00 a.m. on 13 February 1917, they headed to that beacon for all foreign visitors – the Astoria Hotel – only to be told there were no beds. After much wheedling, Harper was given 'a cubbyhole so small that there wasn't even room for my hand luggage'. Thompson, however, was obliged to spend his first night wandering the freezing-cold streets in a blizzard until he was able to find a cheap third-class hotel.

The difficulties of finding accommodation in the city were now extreme. US special attaché James Houghteling had noted that 'Every hotel is jammed and no house or apartment for rent stays on the market for twenty-four hours. Guests sleep in the private dining rooms and the corridors of the hotels, and one can never get a bath before nine a.m. or after nine p.m. because some unfortunate is bedded down in every bath-room.' Arriving in January, he had noted that his own hotel smelt 'like a third-class boarding house in Chicago'.

Much of the desperate shortage of rooms in the capital was a consequence of Germany having issued a threat in mid-January that its submarines would torpedo even neutral ships on sight; no passenger or cargo boats were running from the main terminals into Russia from Norway and Sweden, leaving many foreign nationals and travellers trapped in Petrograd. 'There are hundreds of people waiting here to get away, and hundreds more in Sweden and Norway,' wrote Scottish nurse Ethel Moir. Arriving in Petrograd in January, she and fellow nurse Lilias Grant had found themselves dumped out of the train from the Romanian front, into a 'great steep bank of snow', after which they had struggled with their kit bags to find droshkies, and had then only secured one night in a hotel, sleeping on the floor. After a fruitless search the following day, they appealed to Rev. Lombard at the English Church, who managed to get them rooms at the colony's British Nursing Home. It had been such a pleasure for them, after the rigours of the field hospitals, to spend the evening with Lombard, revelling in 'a real English fire, comfy armchairs, hot buttered toast'. These were 'such unheard-of luxuries', as too was the experience of sleeping 'in real beds and between sheets' again. But they were anxious about getting home: 'It's easier to get into Russia than to get out of it!' wrote Moir. 'And from what we hear, it will become yet more difficult – there are rumours of a revolution on all sides – one hears it everywhere.'

Excerpted from Caught in the Revolution by Helen Rappaport. Copyright © 2017 by Helen Rappaport. Excerpted by permission of St. Martin's Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

I have always imagined that paradise will be a kind of library

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.