Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Petrograd, Russia, 1917 - A World on the Edge

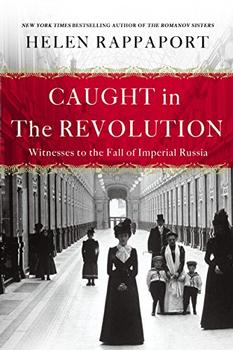

by Helen Rappaport

While waiting to leave the city and get back to the UK, Moir and Grant visited Lady Georgina Buchanan and her daughter Meriel and learned something of the tireless relief work being undertaken in Petrograd by the members of the British colony, particularly with the thousands of refugees fleeing the fighting in their eastern homelands. They were pouring into the Warsaw Station after days crowded into freight cars, and from there were sent to filthy temporary wooden barracks nearby. These were little more than sheds filled with triple or quadruple rows of bunks, housing two to three hundred people each. Other refugees sought shelter in the draughty open hangar that was the station itself – sleeping on the cold stone floors or climbing into empty trucks and freight cars. Some were housed in damp, windowless cellars. Disease was rife, particularly outbreaks of measles and scarlatina; everywhere one looked, the refugees 'lay all day long with expressionless, bulging eyes, half stupefied in the stifling stench of the place.'

The sight of so many pitiful children with insufficient clothing and often no shoes, their bodies and hair crawling with lice, had galvanised a surge of expatriate philanthropic work. Twice a day the lines of refugees formed at the door of the feeding station set up for them, shivering in their rags and waiting for the brass token that entitled them to a piece of black bread and a bowl of English porridge, 'doled out to them by the bustling ladies of the British Colony' and led from the front – as always – by the redoubtable Lady Buchanan. Donations of clothes and shoes for the refugees were sorted at the British embassy by more groups of lady volunteers, whom she had also commandeered; the room used for the purpose, as her daughter Meriel recalled, 'resembled nothing more than an old rag-market'. Not content with her work at the embassy and at the refugee feeding station, Lady Buchanan was also patron of a maternity hospital for Polish refugees in Petrograd, which had been opened by the Millicent Fawcett Medical Unit in Russia, with substantial help from the Tatiana Refugee Committee, named for the Tsar's second daughter, who was its honorary head.

As self-appointed grande dame of the colony's war work, Lady Buchanan had therefore been somewhat put out when her domain was invaded by a rival, in the guise of the small, frail but feisty Lady Muriel Paget. A passionate philanthropist, who had spent nine years running soup kitchens for the poor in deprived parts of London, Lady Muriel was, like the ambassador's wife, from the upper echelons of the aristocracy: a daughter of the Earl of Winchilsea and married to a baronet. Having heard of the appalling casualty rates suffered by the Russian army on the eastern front, Lady Muriel had lobbied a distinguished committee of supporters in the UK, including Alexandra the Queen Mother, for an Anglo-Russian Hospital Unit to be set up in Russia under the auspices of the Red Cross. As its chief organiser, she headed the hospital's team of surgeons, physicians, orderlies and twenty trained and ten volunteer (VAD) nurses; she also had plans for three field hospitals to be established in Russia. Funded by donations from the British public, the hospital had beds for 180 wounded Russian soldiers, or two hundred if the staff pushed the beds closer together. It had been fortunate to secure for its premises Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich's neo-baroque palace, loaned for the duration of the war thanks to some persuasion by Sir George Buchanan.

Located at number 41 Nevsky, on the corner of the Anichkov Bridge opposite the Dowager Empress's palace on the Fontanka River, the palace was a handsome, dark-pink stuccoed building with cream pilasters and surrounds, but its suitability as a hospital left much to be desired. Its drainage was primitive and the plumbing non-existent. Running water, baths and lavatories had to be installed as a matter of urgency, while the lofty, gilded concert hall and two interconnecting large reception rooms were turned into hospital wards. An operating theatre, X-ray department, laboratory and sterilising rooms were created in other partitioned rooms. All the palace's lovely parquet floors were covered in linoleum and the tapestries and damask-silk wall hangings, as well as plasterwork cherub carvings, were masked with plywood.

Excerpted from Caught in the Revolution by Helen Rappaport. Copyright © 2017 by Helen Rappaport. Excerpted by permission of St. Martin's Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The truth does not change according to our ability to stomach it

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.