Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Petrograd, Russia, 1917 - A World on the Edge

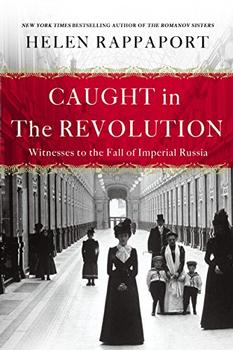

by Helen Rappaport

Lady Buchanan's modest British Colony Hospital on Vasilievsky Island, with its forty-two beds for soldiers and eight for officers, was inevitably eclipsed by the grander and better-funded new Anglo-Russian Hospital, which proudly raised the Union flag above its front door. On 18 January 1916 it had been officially opened by the Dowager Empress and the Tsar's two eldest daughters, Olga and Tatiana, with various other grand duchesses and dukes as well as the Buchanans in attendance. Lady Buchanan had posed for the obligatory group photograph swathed in large hat and furs, but did not disguise her resentment: 'I have nothing to do with the Anglo Russian Hospital,' she would complain to her sister-in-law, 'as Lady Muriel Paget has carefully kept me out of it.' It was just as well, for all Lady Georgina's time was already consumed by her own relief work, which even extended to the mounting of a benefit performance in February of Lady Huntworth's Experiment, by Mrs Waller's Company, a London-based troupe that had been touring Europe – all proceeds going to the purchase of 'warm clothing for the Russian soldiers'.

Lady Georgina was ubiquitous that winter: not just at the embassy workroom and the refugee feeding station, but sorting hospital stores at a Red Cross depot and helping escaped Russian prisoners of war as they arrived back home. 'I have given shirts, socks, tobacco etc to nearly 3000 besides giving them all clothes for their wives and children. They write me such letters of gratitude,' she wrote in a letter home. But by the beginning of 1917 she was complaining of never having 'a moment to sit down, and as for reading a book or any such luxuries one never can indulge in even thinking of the like'. Her hospital was full. No bed was empty for more than a day; 'in fact they telephone every day to ask if we can't possibly take in more … everything is beginning to run short'. The Anglo-Russian Hospital was also besieged. Since opening, it had been rapidly filled to overflowing with serious cases, many of them with terrible septic wounds. In the main these were the result of gas gangrene, the scourge – so surgeon Geoffrey Jefferson observed – of the Russian front. The smell from the suppurating wounds was terrible, for many of the wounded had taken four or five days to be brought to Petrograd from the front. But it was far too cold to throw open the windows for more than a few minutes at a time to clear the air.

Dorothy Seymour, a VAD who had recently transferred to the Anglo-Russian Hospital from nursing on the Western Front, had found her arrival in Petrograd rather disconcerting. The city was 'very smelly, very large and very unwarlike, much more so than London'. The war may have seemed a long way away, but not, however, the heightened sense of social tension that she encountered: 'politics are thrilling out here but it's difficult to get a grasp of them at all, it's such a glorious muddle,' she wrote to her mother. But they were lucky: 'being Red Cross we are very well fed'; they even had the luxury of having their 'hot water bottles filled at night and hot water in the mornings'. As the daughter of a general and granddaughter of an Admiral of the Fleet, and holding an honorary position at court as a Woman of the Bedchamber to Princess Christian, Dorothy was extremely well connected. But she failed to be impressed by the ambassadress: 'Lady G.B. is very sniffy about who she invites and has a deadly household, so nobody takes much notice of her,' she told her mother. Apparently the snobbish Lady Buchanan 'drew the line at VADs' when inviting people to tea, so Seymour cultivated her own contacts on the Petrograd social circuit, going to the ballet, to the opera to see Chaliapin sing Boris Godunov and dining out almost every night with British naval and military attachés – noting with surprise that in wartime Petrograd 'no man changes for dinner'. She counted herself lucky that her work in the bandaging room at the ARH was 'light'. It was difficult enough coping with learning Russian, but for many of the VADs – missing their English Cross & Blackwell jam and having to share cramped, inadequate quarters or spend hours making up bandages at the Winter Palace hospital, instead of nursing – Petrograd was a challenge.

Excerpted from Caught in the Revolution by Helen Rappaport. Copyright © 2017 by Helen Rappaport. Excerpted by permission of St. Martin's Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.