Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

That particular night in the lost history of the world Mr Titus Noone, for that was his name, helped us into our dresses with a sort of manly discretion. Give him his due, he seemed to know about buttons and ribbons and such. He had even had the foresight to sprinkle us with perfumes. This was the cleanest I had been in three years, maybe ever. I had not been noted in Ireland for my cleanliness truth be told, poor farmers don't see baths. When there is no food to eat the first thing that goes is even a flimsy grasp of hygiene.

The saloon filled quickly. Posters had been speedily put up around town, and the miners had answered the call. Me and John Cole sat on two chairs against a wall. Very girl-like, well behaved, sedate, and nice. We never even looked at the miners, we stared straight ahead. We hadn't ever seen too many sedate girls but a inspiration got into us. I had a yellow wig of hair and John had a red one. We musta looked like the flag of some country from the neck up, sitting there. Mr Noone had thoughtfully filled out our bodices with cotton. Okay but our feet were bare, he said he had forgotten shoes in St Louis. They might be a later addition. He said to mind where the miners stepped, we said we would. Funny how as soon as we hove into those dresses everything changed. I never felt so contented in my life. All miseries and worries fled away. I was a new man now, a new girl. I was freed, like those slaves were freed in the coming war. I was ready for anything. I felt dainty, strong, and perfected. That's the truth. I don't know how it took John Cole, he never said. You had to love John Cole for what he chose never to say. He said plenty of the useful stuff. But he never speaked against that line of work, even when it went bad for us, no. We were the first girls in Daggsville and we weren't the worst.

Every citizen knows that miners are all sorts of souls. They come into a country, I seen it a thousand times, and strip away all the beauty, and then there is black filth in the rivers and the trees just seem to wither back like affronted maids. They like rough food, rough whisky, rough nights, and truth to tell, if you is a Indian girl, they will like you in all the wrong ways. Miners go into tent towns and do their worst. There were never such raping men as miners, some of them. Other miners are teachers, professors in more civilised lands, fallen priests and bankrupt storeowners, men whose women have abandoned them as useless fixtures. Every brand and gradation of soul, as the crop measurer might say, and will say. But they all came into Noone's saloon and there was a change, a mighty change. Because we were pretty girls and we were the darlings of their souls. And anyhow, Mr Noone was standing at the bar with a shotgun handy in front of him, in plain sight. You wouldn't believe the latitude the law allows in America for a saloon owner to be killing miners, it's wide.

Maybe we were like memories of elsewhere. Maybe we were the girls of their youth, the girls they had first loved. Man, we was so clean and nice, I wished I could of met myself. Maybe for some, we were the first girls they loved. Every night for two years we danced with them, there was never a moment of unwelcome movements. That's a fact. It might be more exciting to say we had crotches pushed against us, and tongues pushed into our mouths, or calloused hands grabbing at our imaginary breasts, but no. They was the gentlemen of the frontier, in that saloon. They fell down pulverised by whisky in the small hours, they roared with songs, they shot at each other betimes over cards, they battered each other with fists of iron, but when it came to dancing they were that pleasing d'Artagnan in the old romances. Big pigs' bellies seemed to flatten out and speak of more elegant animals. Men shaved for us, washed for us, and put on their finery for us, such as it was. John was Joanna, myself was Thomasina. We danced and we danced. We whirled and we whirled. Matter of fact, end of all we were good dancers. We could waltz, slow and fast. No better boys was ever knowed in Daggsville I will venture. Or purtier. Or cleaner. We swirled about in our dresses and Mr Carmody the storeman's wife, Mrs Carmody of course by name, being a seamstress, let out our outfits as the months went by. Maybe it is a mistake to feed vagrants, but mostly we grew upward instead of out. Maybe we were changing, but we were still the girls we had been in our customers' eyes. They spoke well of us and men came in from miles around to view us and get their name on our little cardboard lists. 'Why, miss, will you do me the honour of a dance?' 'Why, yes, sir, I have ten minutes left at quarter of twelve, if you care to fill that vacancy.' 'I will be most obliged.' Two useless, dirt-risen boys never had such entertainment. We was asked our hands in marriage, we was offered carts and horses if we would consent to go into camp with such and such a fella, we was given gifts such as would not have embarrassed a desert Arab in Arabia, seeking his bride. But of course, we knew the story in our story. They knew it too, maybe, now I am considering it. They were free to offer themselves into the penitentiary of matrimony because they knew it was imaginary. It was all aspects of freedom, happiness, and joy.

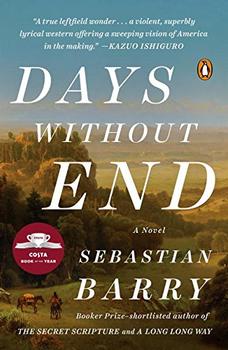

Excerpted from Days Without End by Sebastian Barry. Copyright © 2017 by Sebastian Barry. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

A million monkeys...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.