Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

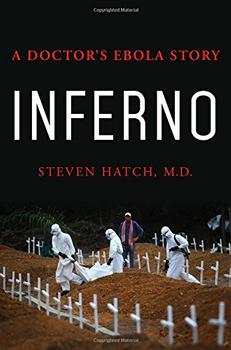

A Doctor's Ebola Story

by Steven Hatch

There were, however, some downsides to following the custom of naming this particular virus Yambuku, especially in a place like rural Africa. Stigmatization was a serious problem. A virus discovered in the late 1960s in a small Nigerian town led to its christening as the Lassa virus, with the consequence that the inhabitants of that place were treated with suspicion and hostility for years afterward. Of the international team, Dr. Karl Johnson, who served as the head of the Centers for Disease Control's Special Pathogens Branch, had proposed sidestepping this problem by naming the virus after a local river. He had done the same the decade before with a deadly virus that caused a disease known as Bolivian Hemorrhagic Fever, giving it the name of Machupo—a tributary of the Amazon. The team favored this approach. They looked on a map, saw a tributary of the Congo known as Ebola, and the name thus took. The name Ebola is from a local Bantu language, Lingala, and means "black river." It was hard to come up with a better name for it than that.

Ebola required another name as well—the class to which it belonged. Viewed under the scanning electron microscope, both Marburg and Ebola had a shape that was completely unlike that of any virus seen before. Most human viruses are roughly spherical in shape, whether HIV, measles, the Hepatitis A, B, and C viruses, and so on. One partial exception is rabies, which if contracted and left untreated is nearly 100 percent lethal, and is thus, along with untreated HIV, technically humankind's most deadly virus. Rabies has a shape that looks almost exactly like a bullet. But Ebola and Marburg have a long, tube-like structure that folds over on itself in erratic ways, each copy of the virus appearing to be slightly different from the next. Not long after Ebola's discovery, a group of scientists proposed the family name of tuburnavirus, from the Latin meaning "tubular virus." Instead, in the early 1980s, a symposium on Ebola and Marburg naming was held by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, the body in charge of providing names and classifications not only to Ebola and Marburg but to all viruses discovered in the world, so that there is some uniformity of nomenclature in the scientific literature. Shortly thereafter, a new proposal to call the family filovirus (from the Latin for "filamentous virus") was submitted to the committee. The concept was the same as that of the name tuburnavirus but was less of a mouthful, and the name stuck.

The mystery deepened. The Sudan outbreak of 1976 would prove to be an Ebolavirus, but although its behavior in humans was roughly similar to that of the Zaire strain—it was, indeed, a little less lethal—its structure was not identical. While the basic internal machinery of the virus was the same, the proteins that coated the surface of the virion were shaped differently. In the laboratory, antibodies that were highly specific for the virus from the Yambuku patients could not latch on to the virus from the Sudanese patients. However, less specific antibodies cross-reacted with both types. Thus, two strains of Ebola had been discovered that year: the Sudan Ebolavirus and the Zaire Ebolavirus. It was the latter that would reappear in Meliandou.

But in 1976, just as quickly as it had begun, the screaming abruptly halted. In 1979, a small outbreak occurred in the town of Nzara, the same location as the original Sudan outbreak. Nearly three dozen people were infected, and two-thirds of them died. After that, however, human Ebola would not be heard from again for more than fifteen years. Then, starting in the mid-1990s, the virus would burst back in terrifying paroxysms that would affect not only Sudan and the now newly named DRC, but also Gabon, Uganda, and the Republic of the Congo. The outbreaks would return almost yearly up to the present day, and these governments in Central Africa would learn to maintain extreme vigilance against the disease.

Excerpted from Inferno by Steven Hatch. Copyright © 2017 by Steven Hatch. Excerpted by permission of St. Martin's Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.