Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

"Thought I heard the baby cry. You should go check on them."

I put my hands in my pockets.

"You don't need my help?"

Pop shakes his head.

"I got it," he says, but then he looks at me for the first time and his eyes ain't hard no more. "You go ahead." And then he turns and goes back to the shed.

Pop must have misheard, because Kayla ain't awake. She's lying on the floor in her drawers and her yellow T-shirt, her head to the side, her arms out like she's trying to hug the air, her legs wide. A fly is on her knee, and I brush it away, hoping it hasn't been on her the whole time I've been out in the shed with Pop. They feed on rot. Back when I was younger, back when I still called Leonie Mama, she told me flies eat shit. That was when there was more good than bad, when she'd push me on the swing Pop hung from one of the pecan trees in the front yard, or when she'd sit next to me on the sofa and watch TV with me, rubbing my head. Before she was more gone than here. Before she started snorting crushed pills. Before all the little mean things she told me gathered and gathered and lodged like grit in a skinned knee. Back then I still called Michael Pop. That was when he lived with us before he moved back in with Big Joseph. Before the police took him away three years ago, before Kayla was born.

Each time Leonie told me something mean, Mam would tell her to leave me alone. I was just playing with him, Leonie would say, and each time she smiled wide, brushed her hand across her forehead to smooth her short, streaked hair. I pick colors that make my skin pop, she told Mam. Make this dark shine. And then: Michael love it.

I pull the blanket up over Kayla's stomach and lie next to her on the floor. Her little foot is warm in my hand. Still asleep, she kicks off the cover and grabs at my arm, pulling it up to her stomach, so I hold her before settling again. Her mouth opens and I wave at the circling fly, and Kayla lets off a little snore.

***

When I walk back out to the shed, Pop's already cleaned up the mess. He's buried the foul-smelling intestines in the woods, and wrapped the meat we'll eat months later in plastic and put it in the small deep-freezer wedged in a corner. He shuts the door to the shed, and when we walk past the pens I can't help avoiding the goats, who rush the wooden fence and bleat. I know they are asking after their friend, the one I helped kill. The one who Pop carries pieces of now: the tender liver for Mam, which he will sear barely so the blood won't run down her mouth when he sends me in to feed it to her; the haunches for me, which he will boil for hours and then smoke and barbecue to celebrate my birthday. A few of the goats wander off to lick at the grass. Two of the males skitter into each other, and then one head-butts the other, and they are fighting. When one of the males limps off and the winner, a dirty white color, begins bullying a small gray female, trying to mount her, I pull my arms into my sleeves. The female kicks at the male and bleats. Pop stops next to me and waves the fresh meat in the air to keep flies from it. The male bites at the female's ear, and the female makes a sound like a growl and snaps back.

"Is it always like that?" I ask Pop. I've seen horses rearing and mounting each other, seen pigs rutting in the mud, heard wildcats at night shrieking and snarling as they make kittens.

Pop shakes his head and lifts the choice meats toward me. He half smiles, and the side of his mouth that shows teeth is knife-sharp, and then the smile is gone.

"No," he says. "Not always. Sometimes it's this, too."

The female head-butts the neck of the male, screeching. The male skitters back. I believe Pop. I do. Because I see him with Mam. But I see Leonie and Michael as clearly as if they were in front of me, in the last big fight they had before Michael left us and moved back in with Big Joseph, right before he went to jail: Michael threw his jerseys and his camouflage pants and his Jordans into big black garbage bags, and then hauled his stuff outside. He hugged me before he left, and when he leaned in close to my face all I could see were his eyes, green as the pines, and the way his face turned red in splotches: his cheeks, his mouth, the edges of his nose, where the veins were little scarlet streams under the skin. He put his arms around my back and patted once, twice, but those pats were so light, they didn't feel like hugs, even though something in his face was pulled tight, wrong, like underneath his skin he was crisscrossed with tape. Like he would cry. Leonie was pregnant with Kayla then, and already had Kayla's name picked out and scrawled with nail polish on her car seat, which had been my car seat. Leonie was getting bigger; her stomach looked like she had a Nerf basketball shoved under her shirt. She followed Michael out on the porch where I stood, still feeling those two little pats on my back, soft as a weak wind, and Leonie grabbed him by the collar and pulled and slapped him on the side of the head, so hard it sounded loud and wet. He turned and grabbed her by her arms, and they were yelling and breathing hard and pushing and pulling each other across the porch. They were so close to each other, their hips and chests and faces, that they were one, scuttling, clumsy like a hermit crab over sand. And then they were leaning in close to each other, speaking, but their words sounded like moans.

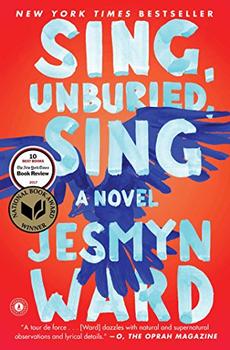

Excerpted from Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward. Copyright © 2017 by Jesmyn Ward. Excerpted by permission of Scribner. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.