Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

As for Vincent, he possessed such an unearthly charm that only hours after his birth a nurse in the maternity ward of Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital had tucked him into her coat in a failed kidnapping attempt. During her trial she'd told the court that the abduction was not her fault. She'd been spellbound, unable to resist him. As time went on, this wasn't an unusual complaint. Vincent was spoiled rotten, treated by Jet as though he were a baby doll and by Frances as if he were a science experiment. If you pinched him, Frances wondered, would he cry? If you offered him a box of cookies, would he make himself sick by eating every one? Yes, it turned out, and yes again. When Vincent misbehaved, which was often, Frances made up stories filled with punishments for little boys who would not do as they were told, not that her cautionary tales stopped him. All the same, she was his protector and remained so even when he was far taller than she.

The school they attended was despised by all three children, though Susanna Owens had worked hard at getting them accepted, throwing cocktail parties for the board of the Starling School at the family's town house. Though their home was ramshackle due to a lack of funds—their father, a psychiatrist, insisted on seeing many of his patients gratis—the place never failed to impress. Susanna staged the parlor for school gatherings with silver trays and silk throw pillows, bought for the event and then returned to Tiffany and Bendel the very next day. Starling was a snobby, clannish establishment with a guard stationed at the front door at Seventy-Eighth Street. Uniforms were required for all students, although Franny regularly hitched up her gray skirt and rolled down the scratchy kneesocks, leaving her freckled legs bare. Her red hair curled in humid weather and her skin burned if she was in the sun for more than fifteen minutes. Franny stood out in a crowd, which irritated her no end. She was tall, and continued to grow until finally in fifth grade she reached the dreaded six-foot mark. She had always had especially long, coltish arms and legs. Because of this her gawky stage lasted for ten years, from the time she was a glum kindergartener, who was taller than any of the boys, until she turned fifteen. Often she wore red boots, bought at a secondhand store. Strange girl, was written in her records. Perhaps psychological testing is needed?

The sisters were outsiders at school, with Jet an especially easy target. Her classmates could make her cry with a nasty note or a well aimed shove. When she began hiding in the girls' bathroom for most of the day, Franny swiftly interceded. Soon enough the other students knew well enough not to irritate the Owens sisters, not if they didn't want to trip over their own shoes or find themselves stuttering when called upon to give a report. There was something about the sisters that felt dangerous, even when all they were doing was eating tomato sandwiches in the lunchroom or searching for novels in the library. Cross them and you came down with the flu or the measles. Rile them and you'd likely be called to the principal's office, accused of cutting classes or cheating. Frankly, it was best to leave the Owens sisters alone.

Franny's only friend was Haylin Walker, who was taller than she by three inches and equally antisocial. He was a legacy doomed to be a Starling student from the moment of his birth. His grandparents had donated the athletic building, Walker Hall, dubbed Hell Hall by Franny, who despised sports. In sixth grade Hay had staged a notorious protest, chaining himself to the dessert rack in the lunchroom to demand better wages for workers in the cafeteria. Franny admired his grit even though the other students simply watched wide-eyed, refusing to join in when Haylin began chanting "Equality for all!"

After the janitor apologetically cut through the chains with a hacksaw, Haylin was given a good talking-to by the headmaster and made to write a paper about workers' rights, which he considered a privilege rather than a punishment. He was obligated to write ten pages, and handed in a tome of nearly fifty pages instead, duly footnoted, quoting from Thomas Paine and FDR. He couldn't wait for the next decade. Everything would change in the sixties, he told Franny. And, if they were lucky, they would then be free.

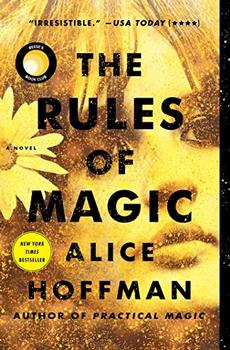

Excerpted from The Rules of Magic by Alice Hoffman. Copyright © 2017 by Alice Hoffman. Excerpted by permission of Simon & Schuster. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.