Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

I swear to Allah, you are the most beautiful girl I have ever seen.

Those weren't the first words he said to me, actually. Before that there was: How do they want that burger cooked? Why are you throwing away those creamers that aren't even used? How old are you?

Almost nineteen, I told him.

What's your name?

Elsie.

I swear to Allah, you are the most beautiful girl I have ever seen.

Bashkim's accent was even worse than my grandparents', who mostly let their twenty-six-inch Panasonic do the talking for them anyway. His voice started so far back in his throat that every word smacked of laryngitis, almost hurt to listen to. And Bashkim wasn't pretty, either, at least not in the bland way that girls like me were supposed to like. His nose and cheeks were as harsh as his voice, all angles and sharp points ready to pierce right through you if you looked him straight on. But his eyes, goddamn. So blue they were almost black, as if the grills in the kitchen had singed a permanent reflection of the butane-blue flame forever licking up under his chin.

"I swear to Allah, you are the most beautiful girl I have ever seen." He bore right into me with that stare, didn't look down while he sliced tomatoes into lopsided wedges that oozed green guts onto his apron.

"Shut up," I said.

"What reason to shut up? Don't you want to be a beautiful girl?"

"I don't care."

"You should care. You should feel lucky you are so pretty. Most people are not so pretty. Most people I don't like to look at so much."

Adem and Fatmir ignored him. The only English they understood was cussing, and anyway, I'd already figured out that the cooks at the Betsy Ross all had their favorite waitresses, wide-hipped single mothers of one or a couple, girls so desperate they heard compliments in the calls of fat ass that followed them out the kitchen doors. Compliments like that earned the cooks blushes, giggly slaps on the wrist, blow jobs in the employees' bathroom before the ten to two o'clock rush. So I guess Adem and Fatmir figured it was finally Bashkim's turn, that it was either shyness or the wife the waitresses told me he'd left back in the old country that had stopped him from calling out before. But what he said, it wasn't fat ass and it wasn't a compliment, not really. It was something more like a threat, at least with those eyes sharpening it into something that jabbed my gut like a switchblade.

"Unless you are ungrateful," he said. "Unless you are a bitch."

He got me on that one, man. Even my mother, Catholic to her core even if she hadn't said a Hail Mary since getting knocked up with me by a Holy Cross High School dropout, would agree it was something close to sin to be ungrateful.

Then Bashkim ignored me for the next three nights, even though I still walked slowly through the kitchen on my way to the employee exit to see if he'd look over. But he said nothing, so I just stepped outside to wait for my mother to pick me up, since I'd broken up with my last ride, Franky, three nights before, the timing not at all coincidental. I didn't know if I could pronounce Bashkim's name right, but even if I got the accents all wrong, it still sounded like a symphony to me compared to Franky. And Franky, not Frank, was his honest given Christian name, which was funny to me before it was embarrassing, although really, what did I have to be embarrassed about? One look at my stringy White Rain hair and yeah right I'd ever be the girlfriend of a boy named Laird or Lawrence or Anything the III. Those boys lived down in Westport or Fairfield and maybe, maybe the worst off of them got sent to Taft, the boarding school fifteen minutes away in Watertown. I bet it was the rich boys with disciplinary problems who got sent there: the rich parents thought their sons would watch the poor bastards who maintained their dorms pull off in dry-rotted Datsuns, and that they would imagine the poor bastards going home to their second-floor apartments on the East End of Waterbury, to their crinkly-eyed twenty-three-year-old common-law wives and their scraggly toddlers with chronic drips of Fudgsicle on their yellow tank tops even though Fudgsicles were too expensive to have in the house, and the troubled rich sons would think, Could that happen to me? though in fact, no, it could not happen to them.

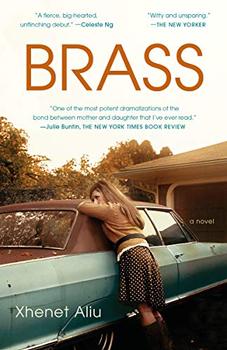

Excerpted from Brass by Xhenet Aliu. Copyright © 2018 by Xhenet Aliu. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.