Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Or you could be them, Meredith says from behind her mittened hands. I say, lead the way, and follow her up the street as she trudges forward with her tongue stretched out to catch falling flakes. Her hair grows a white coat and then turns deep brown as the snow melts. She wipes her nose on her coat sleeve and sniffles. I think she's beautiful even if she doesn't know it yet. She has large lips, a wide mouth and an awkwardly pyramidal nose. She looks like a younger Anne Hathaway.

You should probably kiss her, Adam said to me once as we walked across the Cathedral lawn. She clearly likes you; and honestly it's not that hard, you just move her to one corner of the dance floor and then put your mouth on her mouth, problem solved. Adam is super practical about everything. He's the kind of person who always parks his car in the direction of his house so he doesn't waste extra time when leaving for home. I said, I don't think it works like that. Sure it does, he said, that's how I did it. If she likes me, she should kiss me, I said. It definitely doesn't work like that, Adam said. Then maybe she doesn't like me. Adam smacked his forehead.

A crawling bus packed with miserable-looking people passes us, churning up brown slush in its wake. If the buses are running, there is still a possibility I can take one up to Bradley Boulevard and then walk the last mile home, like I used to do after OJ left for college and before I got my driver's license. It would suck to walk through the snow, especially in my sneakers, but then I'd be home. I stop. What is it, Meredith asks. Her whole face is pale except for the pulsing red at the tip of her nose. Maybe I should just take the bus home, I say, the buses are safe. Fuck that we're halfway there, Meredith says, no fucking way. I try to pull away as Meredith grabs me. She slips on the sidewalk and flails her arms as she tries to find her balance. Her momentum pulls us both down and we laugh even though the cold snow sneaks into my pants. Meredith is right. What is the point of wasting hours on a crawling bus when a warm house and possibly hot chocolate are so close?

Her house is on O Street set back from the road by sloping flower beds filled with twisted brown remnants of fall flowers and decorative grass. They flank steep stone steps. My mother would approve of its understatedness especially because it would remind her of London. My father has never understood the logic behind paying so much money for a small place filled with old plumbing in constant need of repair—even if your neighbors are the senators, cabinet secretaries, and the vast network of unknown but highly influential lobbyists who really run this city. I like the redbrick sidewalks and cobblestone streets better than the large lawns and wooded areas between houses where I live, and it's much closer to school, but I guess the grass is always greener. Normally these streets are full of tourists and students but today they are empty and quiet as the storm settles over the city. I cover my ears with my sleeves as Meredith searches for her keys. Any day now, I say as she kicks her shoes against the bright red door to clean off the snow.

Everything is always life-threatening, Meredith says as the meteorologist on television frantically describes the snow that falls around us. She kneels on the living room couch with her face against the cold window. Her breath fogs the glass. We have eaten turkey and Brie sandwiches because there is nothing else in the fridge and no one will deliver pizza. I understood the turkey, but the Brie with its hard shell tastes of nothing and I have never liked its sticky soft interior. I've told her about the things we eat at home, dried fish that I actually like and tripe that I avoid by hiding beneath the lip of my plate and she has made involuntary faces of disgust followed by an unconvincing, that's cool—I guess. Her parents were supposed to get back from Houston this evening, but all the airports have shut down, says the enthusiastic meteorologist as video of snowplows waiting on the runway at Reagan National Airport streams behind him. Do you want whiskey, she asks before she disappears from the room. She returns with a bottle of amber liquid and she pours a little into her hot chocolate. You can mix it with your hot chocolate, it doesn't taste any different. She takes a sip and a drop falls from her mug to the couch cushion. She blots it into the fabric and then looks at me. You won't get drunk, it's just a drop to help you warm up, she says. I'm not convinced. If we lived in France, she says. If we lived in Saudi Arabia, I say. I don't drink because I'm not twenty-one and because I don't feel the need to drink. My classmates talk about getting wasted at so-and- so's house during their parties on the weekends, but I don't really pay attention. The risks are too high, OJ tells me. You aren't like these people, he says, they can do things that you and I can't do. He never drank and his classmates loved him. He was voted head prefect. He was captain of the soccer team. My teachers still call me by his name. I reach for the bottle and remove the cap. I circle my finger around the rubber stop and touch my lips. The alcohol stings at first and then turns sweet, bringing memories of when I was four and my father had friends over to watch the Nigerian soccer team in the World Cup. I noticed an unattended glass of Coke so I quickly gulped it down, hoping to disappear before someone told me not to. It was more than Coke. It burned all the way down my throat into my belly. I felt my mouth grow hot. I yelped and tried to spit out what I hadn't swallowed. The whole room froze. My father's face became an African mask with exaggerated eyes, nostrils and lips. Then he leapt across the room, grabbed me with one arm and clapped me on the back with a flat palm. The sound broke the tension and made Dad's friends laugh loudly. They stomped and clapped. It drowned out Dad's shouting at me, who told you to come and drink that, enh, while he pressed my body against the sink and made me swallow round after round of water from his cupped palm until my stomach couldn't hold anything more. I vomited watery brown bile into the white sink and all over the countertop. I haven't touched alcohol since then.

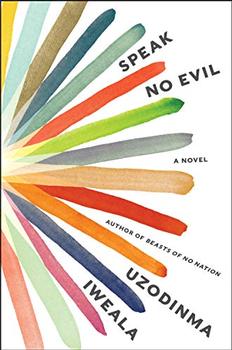

Excerpted from Speak No Evil by Uzodinma Iweala. Copyright © 2018 by Uzodinma Iweala. Excerpted by permission of Harper. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.