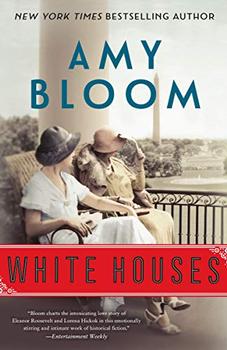

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

I didn't write the story I wanted to and everyone knew it. My boss said to me, Give it up. Go cover Eleanor Roosevelt for a change, her old man's heading to the White House. I didn't say no. Albany was a one-horse town and Eleanor Roosevelt might be dull and pleasant, which is what I'd heard, but I was pretty sure she hadn't killed her own baby and sent an innocent man to fry for it.

She was dull and pleasant for the first five minutes. I sat right next to her in a faded velvet chair, in the old-fashioned drawing room of the Governor's Mansion on Eagle Street, and looked at her cheap, sensible serge dress and flat shoes and thought, Who in the name of Christ has dressed you? I looked closely, to make notes, and then I looked away to be polite. She poured tea and I did notice her beautiful hands and her very plain wedding band, a little loose on her finger. We chatted. We sipped. I made some remarks about Republicans and she laughed, and not politely.

She asked me about the Lindbergh case and I told her about what I'd seen and she shook her head over Lindbergh. I prefer Amelia Earhart, she said. You know, she was a social worker, before she was a pilot. That's not all she was, I thought, but I ate a cookie.

We talked about the great state of New York and the needs of its people and then it was time for dinner and we had a sherry-spiked mushroom soup I can still taste. We ate and talked until late. She told me that her husband believed that the role of government was to help people. I nodded. All people, she said. She told me about Louis Howe, Governor Roosevelt's campaign manager, whom she had come to admire. I didn't at first, she said. She said some people thought he was a Machiavelli. She said he was coarse and direct and deeply, deeply political. But Louis Howe is also, she said, the kindest, most loyal, most decent person I know. When my husband got polio—she put her hand over her mouth. Please don't write that, she said. That is not the kind of thing I wish to discuss, in the newspapers. I made a big show of striking a line. We'll go with Louis Howe and his fine qualities, I said. Now, give me something uplifting, so we go out on a positive note about the governor and his race for the White House.

"The function of democratic living is not to lower standards but to raise those that have been too low."

"That's very good," I said.

She rang a bell and said, Would you care for a sherry? Her eyes were light blue, then dark blue, lake blue. I saw a quick flare, a pilot light of interest come and go.

I put away my notebook and we sat, sipping sherry, listening to opera, until a maid came in and asked if she should get my coat.

I said, Mrs. Roosevelt, I hate to go, but I have a story to file. She said, Don't make me sound like a fool, Miss Hickok. I said that I couldn't if I tried and she said she thought that was the first lie I'd told her. We both stood up and she helped me on with my coat. We looked at each other in their grand, gold-framed mirror and she adjusted my hat. Then she said, We're grown women, both doing our jobs. Call me Eleanor. I smiled all the way home.

We saw each other every week of the campaign and I liked what I saw so much, I offered to cover her full-time for the Associated Press as Roosevelt's race for the White House heated up. My editor liked the pieces and every once in a while he'd say, Your lady's got some good lines. I liked her height and her energy. I liked her long, loose stride and her progressive principles. She insulted conservatives and cowards every time she opened her mouth and I wrote it all down. She smiled when she saw me coming and I did the same. When we had breakfast together, I sometimes took a sausage off her plate.

She called me at the end of October and told me that Franklin's secretary's mother had died. I'd already met Missy LeHand, the governor's executive secretary, his lodestar of competence and tact and likely something more. Dozens of reporters, including me, saw Missy sitting very close to Governor Roosevelt, late at night, rubbing his shoulders. Eleanor said she didn't want to make the trip to Potsdam, New York, with just dear, bereft Missy and Franklin certainly wasn't going to attend that shit storm of weeping, hopeful women (which was not how Eleanor put it). She said, Won't you come with us, Hick? It's quite a long ride, we'll get better acquainted and then we'll tour a power plant. We can go see where they want to put the Saint Lawrence Seaway.

Excerpted from White Houses by Amy Bloom. Copyright © 2018 by Amy Bloom. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.