Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

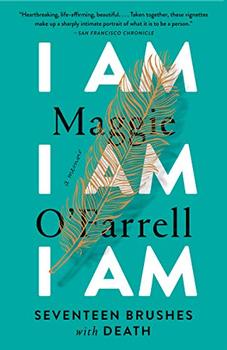

Seventeen Brushes with Death

by Maggie O'Farrell

We practised reversing our elbows into the throats of our imaginary assailants, rolling our eyes as we did so because we were, after all, teenage girls. We took it in turns to rehearse the loudest shout we could. We repeated, dutifully, dully, the weak points in a male body: eye, nose, throat, groin, knee. We believed we had it covered, that we could take on the lurking stranger, the drunk assailant, the bag-snatching mugger. We were sure we'd be able to break their grip, bring up our knee, scratch at their eyes with our nails; we reckoned we could find an exit out of these alarming yet oddly thrilling synopses. We were taught to make noise, to attract attention, to yell, POLICE. We also, I think, imbibed a clear message. Alleyway, nightclub, pub, bus-stop, traffic lights: the danger was urban. In the country, or in rural towns like ours—where there were no nightclubs, no alleyways and no traffic lights, even—things like this did not happen. We were free to do as we pleased.

And yet here is this man, high up a mountain, blocking my way, waiting for me.

It seems important not to show my fear, to play along. So I keep walking, keep putting one foot in front of the other. If I turn and run, he could catch up with me in seconds and there would be something so exposing, so final about running. It would uncover to us both what this situation is; it would bring things to a head. The only option seems to be to carry on, to pretend that this is perfectly normal.

"Hello again," he says to me, and his gaze slides over my face, my body, my bare, muddy legs. It is a glance more assessing than lascivious, more calculating than lustful: it is the look of a man working something out, planning the logistics of a deed.

I cannot meet his gaze, I cannot look at him directly, not quite, but I am aware of narrow-set eyes, a considerable height, ivory-coloured incisors, fists gripping his rucksack straps. I have to clear my throat to say, "Hi." I think I nod. I turn myself sideways so as to step past him: a sharp mix of fresh sweat, leather from his rucksack, some kind of chemical-heavy shaving oil that seems distantly familiar.

I am past him, I am walking away, the path is open before me. He has, I note, chosen for his ambush the apex of the hike: I have climbed and climbed, and it is at this point that I will start to descend the mountain, to my guesthouse, to my evening shift, to work, to life. It's all downhill from here.

I am careful to use strides that are confident, purposeful, but not frightened. I am not frightened: I say this to myself, over the oceanic roar of my pulse. Perhaps, I think, I am free, perhaps I have misread the situation. Perhaps it's perfectly normal to lie in wait for young girls on remote paths and then let them go.

I am eighteen. Just. I know almost nothing.

I do know, though, that he is right behind me. I can hear the tread of his boots, the swishing movement of his trouser fabric—some kind of breathable, all-weather affair.

And here he is again, falling into step beside me. He walks closely, intimately, his arm at my shoulder, the way a friend might, the way I walked home from school with classmates.

"Lovely day," he says, looking into my face. I keep my head bowed. "Yes," I say, "it is." "Very hot. I might go for a swim." There is something peculiar about his diction, I realise,

as we tread the path together with rapid, synchronised steps. His words halt mid-syllable; his rs are soft, his ts over-enunciated, his tone flat, almost expressionless. Maybe he's slightly "touched," as the expression goes, like the man who used to live down the road from us. He hadn't thrown anything out since the war and his front garden was overrun, like Sleeping Beauty's castle, with ivy. We used to try to guess what some of the leaf-draped objects were: a car, a fence, a motorbike? He wore knitted hats and patterned tank tops and too-small once-smart suits that were coated with cat-hair. If it was raining, he slung a bin liner over his shoulders. Sometimes he would come to our door with a zipped bag full of kittens for us to play with; other times he would be drunk, livid, wild- eyed and ranting about lost postcards, and my mother would have to take him by the arm and lead him home. "Stay there," she would say to us, "I'll be back in a tick," and she'd be off down the pavement with him.

Excerpted from I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O'Farrell. Copyright © 2018 by Maggie O'Farrell. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.