Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

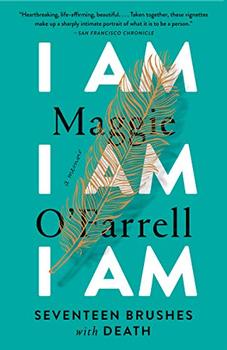

Seventeen Brushes with Death

by Maggie O'Farrell

Maybe, I think, with a flood of relief, that's all this means. This man might be like our old neighbour: eccentric, different, now long dead, his house cleared and sanitised, the ivy hacked down and burnt. Perhaps I should be kind, as my mother was. I should be compassionate.

I turn to him then, as we walk together, in rapid step, beside the lake. I even smile.

"A swim," I say. "That sounds nice."

He answers by putting his binocular strap around my neck.

A day or so later, I walk into the police station in the nearby town. I wait in line with people reporting lost wallets, stray dogs, scraped cars.

The policeman at the desk listens, head cocked to the side. "Did he hurt you?" is his first question. "This man, did he touch you, hit you, proposition you? Did he do or say anything improper?"

"No," I say, "not exactly, but—" "But what?" "He would have done," I say. "He was going to." The man looks me up and down. I'm wearing patched

cut-offs, numerous silver hoops through the cartilage of my ears, tattered sneakers, a T-shirt with a picture of a dodo and the words "Have you seen this bird?" on it. I have a mane—there isn't really any other word to describe it—of wild hair into which a guest, a serene-faced Dutch woman, who had travelled to the guesthouse with her harp and a felting kit, has woven beads and feathers. I look like what I am: a teenager who has been living alone for the first time, in a caravan, in a forest, in the middle of nowhere.

"So," the policeman says, leaning heavily on his papers, "you went for a walk, you met a man, you walked with him, he was a bit peculiar, but then you got home okay. Is that what you're telling me?"

"He put," I say, "the strap of his binoculars around my neck."

"And then what?"

"He ..." I stop. I hate this man with his thick eyebrows, his beery paunch, his impatient stubby fingers. I hate him more, perhaps, than the man beside the tarn. "He showed me some ducks on the lake."

The policeman doesn't even try to hide his smile. "Right," he says, and shuts his book with a snap. "Sounds terrifying."

How should I have articulated to this policeman that I could sense the urge for violence radiating off the man, like heat off a stone? I have been over and over that moment at the desk in the police station, asking myself, was there anything I could have done differently, anything I might have said that would have changed what happened next?

I could have said: I want to see your supervisor, I want to see the person in charge. I would do this now, age forty-three, but then? It didn't occur to me it was possible.

I could have said: Listen to me, that man didn't hurt me but he will hurt someone else. Please find him before he does.

I could have said that I have an instinct for the onset of violence. That, for a long time, I seemed to incite it in others for reasons I never quite understood. If, as a child, you are struck or hit, you will never forget that sense of your own powerlessness and vulnerability, of how a situation can turn from benign to brutal in the blink of an eye, in the space of a breath. That sensibility will run in your veins, like an antibody. You learn fairly quickly to recognise the approach of these sudden acts against you: that particular pitch or vibration in the atmosphere. You develop antennae for violence and, in turn, you devise a repertoire of means to divert it.

The school I went to seemed steeped in it. The threat, like smoke, filled the corridors, the halls, the classrooms, the aisles between desks. Heads were smacked, ears were gripped, chalk dusters were thrown, with smarting accuracy; one teacher had the habit of picking up kids he didn't like by the waistbands of their trousers and launching them at the walls. I can still recall the sound of child cranium hitting Victorian tile.

For the worst offences, boys were sent to the headmistress, where they were given the cane. Girls got the dap. I used to look at my daps—those black canvas shoes with a horseshoe of elastic across the front that we were made to wear when climbing over gym horses—and in particular their greyish rippled soles and imagine the impact: rubber on exposed flesh.

Excerpted from I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O'Farrell. Copyright © 2018 by Maggie O'Farrell. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.