Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Story of War and What Comes After

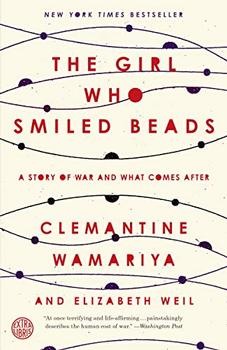

by Elizabeth Weil, Clemantine Wamariya

In this nice studio, in front of all these well-dressed people, Oprah's team played the video of Oprah and Elie Wiesel walking arm in arm through snow-covered Auschwitz, discussing the Holocaust.

Then the producers gave us a break. We sat in silence. Some of us were horrified and others were crying.

After that, Oprah said glowing things about all the winners of the essay contest except me. I told myself this was fine. Fine. I hadn't really gone to school until age thirteen, and when I was seven I'd celebrated Christmas in a refugee camp in Burundi with a shoebox of pencils that I'd buried

under our tent so that nobody would steal it. Being in the audience was enough, right? Plus, I kept wanting to say to Oprah: Do you know how many years, and across how many miles, Claire has been talking about meeting you?

But then Oprah leaned forward and said, "So, Clemantine, before you left Africa, did you ever find your parents?"

I had a mike cord tucked under my black TV blazer and a battery pack clipped to my black TV pants, so I should have suspected something like this was coming. "No," I said. "We tried UNICEF ... , we tried everywhere, walking around, searching and searching and searching."

"So when was the last time you saw them?" she asked.

"It was 1994," I said, "when I had no idea what was going on."

"Well, I have a letter from your parents," Oprah said, as though we'd won a game show. "Clemantine and Claire, come on up here!"

Claire held on to me. She was shaking, but she kept on her toughest, most skeptical face, because she knows more about the world than I do, and also because she refused to think, even after all we'd been through, that anybody was better or more important than she was. When we were dirt poor and alone, she'd be in her seventh hour of scrubbing someone's laundry by hand and she'd see on a TV an image of Angelina Jolie, swaggering and gleaming, radiating moral superiority, and even then Claire would say, "Who is that? God? You, you're human. Nothing separates me from you."

I have never been Claire. I have never been inviolable. Often, still, my own life story feels fragmented, like beads unstrung. Each time I scoop up my memories, the assortment is slightly different. I worry, at times, that I'll always be lost inside. I worry that I'll be forever confused. But that day I leapt up onto the set, smiling. One of the most valuable skills I'd learned while trying to survive as a refugee was reading what other people wanted me to do.

"This is from your family, in Rwanda," Oprah said, handing me an envelope. She looked solemn, confident in her purpose. "From your father and your mother and your sisters and your brother."

Claire and I did know that our parents were alive. We knew they'd lost everything—my father's business, my mother's garden—and that they now lived in a shack on the outskirts of Kigali. We talked to them on the phone, but only rarely because—how do you start? Why didn't you look harder for us? How are you? I'm fine, thanks, I've been working at the Gap and I've found it's much easier to learn to read English if you also listen to audiobooks.

I opened the envelope and pulled out a sheet of blue paper. Then Oprah put her hand on mine to stop me from unfolding the letter. It was a huge relief. I didn't want to have a breakdown on TV.

"You don't have to read it right now, in front of all these people," Oprah said. "You don't have to read it in front of all these people ..." She paused, master of stagecraft that she is. "Because ... because ... your family ... IS HERE!"

I started walking backward. Claire's jaw unhinged in a caricature of shock. Then a door that had images of barbed wire on it—created especially for this particular episode, I assume, to evoke life in an internment camp—opened stage right and out came an eight-year-old boy, who was apparently my brother. He was followed by my father, in a dark suit, salmon shirt, and tie; a shiny new five-year-old sister; my mother in a long blue dress; and my sister Claudette, now taller than me. I'd last seen her when she was two years old and I still believed my mother had picked her up from the fruit market.

Excerpted from The Girl Who Smiled Beads by Clemantine Wamariya and Elizabeth Weil. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.