Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

The world around us was named Scarborough. It had once been called "Scarberia," a wasteland on the outskirts of a sprawling city. But now, as we were growing up in the early '80s, in the heated language of a changing nation, we heard it called other names: Scarlem, Scarbistan. We lived in Scar-bro, a suburb that had mushroomed up and yellowed, browned, and blackened into life. Our neighbours were Mrs. Chandrasekar and Mr. Chow, Pilar Fernandez and Clive "Sonny" Barrington. They spoke different languages, they ate different foods, but they were all from one colony or the other, and so they had a shared vocabulary for describing feral children like us. We were "ragamuffins." We were "hooligans" up to no good "gallivanting." We were what one neighbour, more poet than security guard, described as "oiled creatures of mongoose cunning," raiding dumpsters and garbage rooms or climbing up trees and fire-exit stairs to spy on adults. During winters we snowballed cars on Lawrence Avenue, dipping into the back alleys if the drivers tried to pursue us. A Pinto Wagon once shaving past my face, its wake tugging hard upon my body, Francis's hand upon my shoulder pulling me safe.

During the day, we had more formal educational opportunities. Our school was named after Sir Alexander Campbell, a Father of Confederation. But we the students of his school had our own confederations, our own schoolyard territories and alliances, our own trade agreements and anthems. We listened to Planet Rock and carried Adidas bags and wore stonewashed jeans and painter caps. You could hear us whenever there were general assemblies in the auditorium, our collective voices overwhelming whatever politely seated ceremony we were supposed to be attending.

Hey Francis, homeboy, my man.

Rudebwoy Francis! Gangstar!

Francis and I each served out long sentences in classrooms beneath the chemical hum of white fluorescent lights, in part out of fear of our mother, who warned us, upon pain of something worse than death, not to squander "our only chance." But Francis actually liked to learn. He read books, and he was a good observer.

And after class was out there were other institutions to learn from. A dozen blocks west of the towers and housing complexes of the Park, at the intersection of Markham and Lawrence, there lay a series of strip malls. There were grocery shops selling spices and herbs under signs in foreign languages and scripts, vegetables and fruits with vaguely familiar names like ackee and eddo. There were restaurants with an average expiry date of a year, their hand-painted signs promising ice cream with the "back home tastes" of mango and khoya and badam kulfi, a second sign written urgently in red marker promising that they'd also serve, whenever asked, the mystery of "Canadian food."

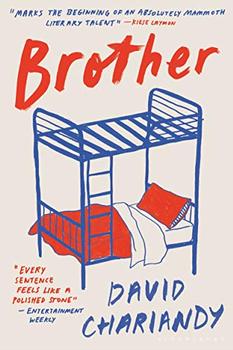

Excerpted from Brother by David Chariandy. Copyright © 2018 by David Chariandy. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.