Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Discuss | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

If his devotion was total, its origin remained a mystery. As a child, he had gazed with wonder at the wax cadavers at the Anatomical Museum, but so had his three brothers, and not one of them had turned to Hippocrates's art. There were no doctors in his line, not among the Krzelewskis of southern Poland, and certainly not among his mother's people. At times, cornered by some peahen at one of her unbearable receptions, he endured a condescending speech on how medicine was a noble calling, that one day he would be rewarded for his kindness. But kindness was not interesting to him. His best answer to what drove his endless hours of study was the joy of study itself. He was not a person drawn to religious devotion, but it was in religion that he found the words: revelation, epiphany, the miracle of God's creations, and by extension, the miracle of how God's creations failed.

Study itself: this was, at least, the answer that he gave in his moments of greatest exultation. But there was another reason he had turned to medicine, one he only considered later in the hours of his doubt. Of the two other students he could call his friends, Feuermann was the son of a tailor, while Kaminski, who wore empty spectacles just to look older, was on a scholarship from the Sisters of Mercy. Although they never spoke of it, Lucius knew they all had come to medicine for its promise of social mobility. For Feuermann and Kaminski this meant up: from the slums of Leopoldstadt and the charity school. For Lucius, whose father came from an ancient Polish family that claimed descent from Japheth, son of Noah (yes, that Noah), and in whose mother's veins coursed the same cerulean blood as that Great Liberator of Vienna and Savior of Western Civilization, Jan Sobieski, King of Poland, Grand Duke of Lithuania, Ruthenia, Prussia, Masovia, Samogitia, Livonia, Smolensk, Kiev, Volhynia, etc., etc.—for Lucius, such mobility meant not up, but out.

No, from the beginning he hadn't belonged among them, an accidental sixth child born years after the doctor told his mother she couldn't conceive again. Were he not the spitting image of his father—tall and big-pawed, with skin pale as alabaster, a shock of blond hair fit for an Icelander, and old man's ducktail eyebrows even as a little boy—he might have wondered if he was another's child. But the flushes of ruddiness that gave his father the hale glow of a knight who has just removed his jouster's helmet, in Lucius looked more like blotches of an embarrassed blush. Watching his brothers and sisters glide through his mother's receptions, he could never understand their ease, their grace, their force. No matter what he tried—holding a stone in his pocket as a reminder to smile, writing lists of "Chatting Topics"—spontaneity eluded him. Before the parties, he would slink through the salon, attaching to each piece of artwork an idea for conversation: when he saw the portrait of Sobieski he was to speak of holidays; the bust of Chopin should spur him to ask about his guest. Yet, no matter how he prepared, it happened: there would be a moment, a pause—just a second—just a catch—before he—spoke. He could move easily through the shifting choreography of soft gowns and pressed field marshal trousers. But the moment that he approached a cluster of other children, their laughter stopped.

He wondered if he had grown up in another time or place—among a different, silent people—his discomfort would never have been noticed. But in Vienna, among the eloquent, where frivolity had been cultivated into a faith, he knew that others saw him falter. Lucius: the name, chosen by his father after the legendary kings of Rome, itself was mockery; he was anything but light. By his thirteenth birthday, so terrified by his mother's disapproval, so increasingly uncertain of anything to say at all, his unease began to appear in a quiver of his lip, a nervous twisting of his fingers, and at last, a stutter.

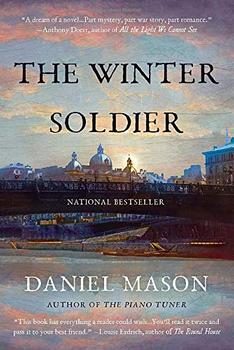

Excerpted from The Winter Soldier by Daniel Mason. Copyright © 2018 by Daniel Mason. Excerpted by permission of Little Brown & Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.