Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Discuss | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

In the beginning, he had been accused of feigning. Stutters appear in childhood, his mother told him, not in a boy his age. He didn't stutter when he was alone, nor when he spoke of his science magazines or the bird's nest outside his window. Nor did it afflict him at the aquarium in the Imperial Zoological Collections, where he went to stare for hours at the Grottenolm, blind, translucent salamanders from the Southern Empire, in whom one could watch the magical pulsing of their blood.

But at last, conceding that something might be wrong, she hired a speech expert from Munich, famous for his Textbook of the Disorders of Speech and Language and a metal device called the Zungenapparat, which isolated the labial, palatal, and glottal movements from one another and so promised the repair of sound and speech.

The doctor arrived on a warm summer's morning, gnawing a hangnail. Humming, he appraised the child, palpating his neck and peering into his ears. There were measurements, sour fingers probed his gums; his mother grew bored and left. At last, the apparatus was applied, and the boy was told to sing "The Happy Hiker."

He tried. The clamp pinched his lips. The tongue prongs cut, and he spat blood. "Louder!" cried the doctor. "It is working!" His mother returned to find her son baying like a dog, mouth foaming red. Lucius looked between them—Mother—Doctor—Mother—Doctor—as his mother seemed to grow bigger and pinker and the doctor smaller and paler. Oh, you have no idea what you have gotten yourself into, thought the boy, watching the man. And he began to giggle—not an easy task with a Zungenapparat—as the doctor gathered up his tools and fled.

A second doctor tried to hypnotize him, failed, and prescribed herring for oral lubrication. A third, cupping his testicles, declared them sufficient, but finding no movement when the boy was shown the fleshy gymnastics in an illustrated edition of True Secrets of the Convent, he removed his notebook and scrawled "Insufficiency of the Gland." Then he whispered to Lucius's mother.

A week later, she had his father take him to a house specializing in virgins, certificated free of syphilis, where he was locked in the plush Ludwig II suite with a country girl from Croatia attired like a singer of the opera buffa. As she was from the south, Lucius asked her if she had heard of the Grottenolm. Yes, she said, her frightened face brightening. Her father had once collected the little salamanders to sell to aquaria across the Empire. Then the two of them marveled at this coincidence of their lives, for, just that week, one of Lucius's favorites in the Zoological Collection had spawned.

Afterward, when his father asked, "And did you do it?" Lucius answered, "Yes, Father." And his father, "I don't believe you. What did you do?" And Lucius, "I did what was to be done." And his father, "Which is what?" And Lucius, "What I have learned." And his father, "What have you learned, boy?" And Lucius, remembering a novel of his sister's, answered, "I have done it in a fiery way."

"That's my son," his father said.

In silence, he endured his parents' receptions until they allowed him to escape. He would have skipped them altogether, but his mother said the guests would think she was like Walentyna Rozorovska, who hid her crippled daughter in a crate. So Lucius followed as she made her rounds. She was distinctly proud of her narrow waist, and he thought she sometimes kept him near because nothing pleased her more than to have another woman say: "Agnieszka, after six children—so sportive! How can it be?"

Whalebone! Lucius wished to shout. The conversation horrified him. He thought such comments about his birth were vulgar, as if they were complimenting her on her genitalia. He was relieved when she spoke instead of music and architecture, and showed particular interest in the industrialists' wives and where their husbands had been traveling, and it was only when he was older that he realized how strategic, and ultimately ruthless, such questioning had been.

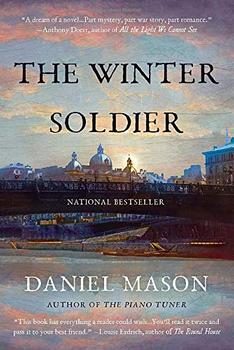

Excerpted from The Winter Soldier by Daniel Mason. Copyright © 2018 by Daniel Mason. Excerpted by permission of Little Brown & Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.