Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Discuss | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

The lecturer that day, Grieperkandl, the great anatomist, was of that species of emeriti who believed that most modern medical innovations (such as handwashing) were emasculating. It was in a state of general terror that the students attended his classes, for each week Grieperkandl would call a Praktikant before him, take down his name in a little notebook (always a his; there were but seven women in the class, and Grieperkandl treated them all as nurses), and proceed to submit him to an inquisition of such clinically irreverent arcana that most of their professors would have failed.

It was during a lecture of the anatomy of the hand that Lucius was called to the front of the class. Grieperkandl asked if he had studied for that day—he had—and whether he knew the name of the bones—he did—and whether he would like to recite them. The old professor was standing so close that Lucius could smell the naphthalene on his coat. Grieperkandl rattled his pocket. Inside he had some bones. Would Lucius like to select one and name it? Lucius hesitated; there was nervous laughter in the tiers. Then cautiously, he slid his hand in, his fingers settling on the longest and thinnest of the bones. As he went to remove it, the professor grabbed his wrist. "Any fool can look," he said. And Lucius, closing his eyes, said scaphoid, and withdrew it, and Grieperkandl said, "Another," and Lucius said capitate and withdrew it, and Grieperkandl said, "Those are the two largest—that is easy," and Lucius said lunate, and Grieperkandl, "Another," and Lucius said hamate, triquetrum, metacarpal, removing each in turn until at last a tiny bone remained, peculiar, too stubby to be a distal phalange, even that of the thumb.

"Toe," said Lucius, realizing he had sweated through his shirt. "It's the pinkie toe."

A hush had come over the class.

And Grieperkandl, unable to prevent a yellow smile from spreading across his face (for, he would say later, he had been waiting twenty-seven years to make the joke), said, "Very good, my son. But whose?"

An unusual aptitude for the perception of things that lie beneath the skin. He copied out these words into his journal, in Polish, German, and Latin, as if he'd found his epitaph. It was a bracing thought for a boy who had grown up mystified by the simplest manners of other people. What if his mother's pronouncements were false? What if all along he had been simply seeing deeper? When the first Rigorosum came after two years, he scored the highest in the class on all his subjects but physics, where Feuermann edged him out. It seemed impossible. With his governess, he had nearly given up on Greek, cared nothing for the causes of the War of the Austrian Succession, confused Kaiser Friedrich Wilhelm with Kaiser Wilhelm and Kaiser Friedrich, and thought philosophy stirred up problems where there were no problems before.

He entered his fifth semester with great anticipation. He had enrolled in Pathology, Bacteriology, and Clinical Diagnosis, and the summer would bring the first lectures in Surgery. But his hopes to leave his books and treat a real, living patient were premature. Instead, in the same vast halls where he had once attended lectures on organic chemistry, he watched his professors from the same great distance. If a patient was brought before them—and even this was rare in the introductory classes—Lucius could scarcely see them, let alone learn how to percuss the liver or palpate swollen nodes.

Sometimes he was called forth as Praktikant. In Neurology, he stood next to the day's patient, a seventy-two-year-old locksmith from the Italian Tyrol, with such severe aphasia that he could only mutter "Da." His daughter translated the doctor's questions into Italian. As the man tried to answer, his mouth opened and closed like a baby bird. "Da. Da!" he said, face red with frustration, as murmurs of fascination and approval filled the hall. Driven on by the lecturer's aggressive questioning, Lucius diagnosed a tumor of the temporal lobe, trying to keep his thoughts on the science and away from how miserable he was making the old man's daughter. She had begun to cry, and she kept reaching for her father's hand. "You will stop that!" his professor shouted at her, slapping her fingers. "You will disturb the learning!" Lucius's face was burning. He hated the doctor for asking such questions before the daughter, and he hated himself for answering. But he also did not like feeling that he was on the side of the patient, who was inarticulate and weak. So he answered forcefully, with no compassion. His diagnosis of early brainstem herniation and the relentless destruction of the breathing centers and death, was met by rising, even thunderous, applause.

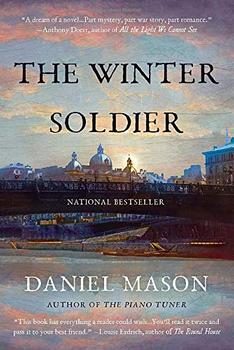

Excerpted from The Winter Soldier by Daniel Mason. Copyright © 2018 by Daniel Mason. Excerpted by permission of Little Brown & Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.