Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Discuss | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Certain affections have an unfortunate destiny.

1.

Northern Hungary,

February 1915

They were five hours east of Debrecen when the train came to a halt before the station on the empty plain.

There was no announcement, not even a whistle. Were it not for the snow-draped placard, he wouldn't have known they had arrived. Hastening, afraid he would miss the stop, he gathered his bag, his coat, his saber, pushing his way out through the men who filled the corridor of the train. He was the only passenger to descend. Farther down the line, porters unloaded a pair of crates onto the snow before jumping back on board, slapping warmth into their hands. Then the carriages began to move, chains clanking, stirring his greatcoat and swirling snow around his knees.

He found the hussar in the station house, with the horses brought in from the cold. Their ears flicked against the low ceiling, their long faces overhanging a bench where three peasant women sat, hands clasped over their swaddled bellies like fat men content after a meal. Feet dangling just above the floor. Woman, horse, woman, horse, woman. The hussar stood without speaking. Back in Vienna, Lucius had seen regiments on parade with their plumes and colored sashes, but this man was dressed in a thick grey coat, with a cap of worn, patched fur. He motioned Lucius forward and handed him the reins of one of the horses before he led the other outside, its tail whisking across the women as it passed beneath the Habsburg double-headed eagle on the door.

Lucius tugged on the reins, but his horse resisted. He stroked her neck with the back of one hand—the broken one—while he pulled with the other. "Come," he whispered, first in German, then in Polish, as her back hooves broke from the ice and frozen dung. To the hussar at the door, he said, "You've been waiting long."

It was the last thing he said. Outside, the hussar lowered a leather mask, cut with slits for eyes and nostrils, and heaved himself onto his horse. Lucius followed, rucksack on his shoulders, struggling to wrap his scarf over his face. From inside the station house, the three old women watched them until the hussar wheeled his horse around and kicked the door shut. Your sons aren't coming, Lucius wanted to tell them. Not in any state you'd wish to see. There was scarcely a man with two legs who wasn't trying to lift the Russian siege of Przemysl now.

Without a word the hussar began to ride north at a trot, his long rifle across his saddle, his saber on his waist. Lucius looked back to the railway, but the train had vanished. Snowflakes had begun to cover the track.

He followed. His horse's hooves clattered on the frozen earth. The sky was grey, and in the distance, he could see the mountains rising up into the storm. Somewhere, there, was Lemnowice, and the regimental hospital of the Third Army where he was to serve.

* * *

He was twenty-two years old, restless, resentful of hierarchy, impatient for his training to come to an end. For three years he had studied alone in the libraries, devoted to medicine with a monastic severity. Onion paper feathered the margins of his textbooks, licked and pasted in by hand. In the great halls, on gleaming lantern slides, he'd seen the ravages of typhus, scarlatina, lupus, pest. He had memorized the signs of cocainism and hysteria, knew that the breath of cyanide poisoning smelled of almonds, and the murmur of a narrowed aortic valve could be heard in the neck. In tie and jacket, freshly ironed for the day, he'd spent hours staring down from the dizzying heights of the surgery theater, straining his neck for a line-of-sight through the restless coveys of his classmates, over the neatly combed heads of senior students, over the junior professors, the surgeon's assistants, across the surgical drape, and down into the cut. By the time war was declared, he was dreaming nightly of the theater: long, demanding dreams in which he extracted impossible organs, half-man, half-pig. (It was on butcher's scraps he practiced.) One night, dreaming of an extraction of the gallbladder, he had such a distinct impression of the wet, leaden warmth of the liver, that he woke certain he could carry out the surgery alone.

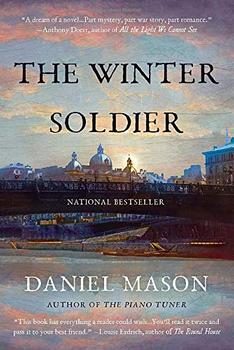

Excerpted from The Winter Soldier by Daniel Mason. Copyright © 2018 by Daniel Mason. Excerpted by permission of Little Brown & Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.