Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

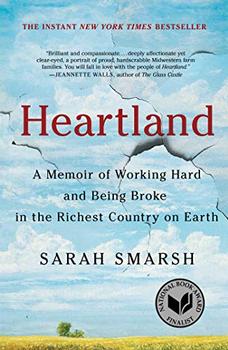

A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth

by Sarah Smarsh

Nick was the youngest of six children—three boys and three girls. He was given his dad's full name, Nicholas Clarence, even though he was the third-born son, like his parents had run out of ideas. When he came along, his dad was forty-six and his mother, Teresa, was forty-one. He was probably a bit of a surprise. But his parents were both Catholic and farm people, groups that had different but intertwining reasons for producing a lot of children—the former thinking birth control sinful, the latter needing help raising wheat.

True to his birthday, Nick turned out to be a worker among workers. His productivity and money saving impressed even his stingy parents, who had come of age during the Great Depression. Before he was old enough to drive, he owned more head of cattle than his dad did. At age nineteen, he started a foundation-laying business. When he met Jeannie in his early twenties, he already had five employees and a few thousand dollars in the bank.

Jeannie had book smarts and was a talented artist, but, like Nick, her handiest sort of intelligence was with life, with money. She could always find her way out of a bind, hustling cash with odd jobs, making money stretch the furthest it could. She came from a long line of women whose lives amounted to getting out of a bind, often by working harder than their men. Nothing disgusted Jeannie more than a man sitting on his butt all day expecting to be taken care of. She respected how Nick worked and said "please" and "thank you."

Jeannie and Nick looked good together. She was small and fair-skinned with long, straight brown hair parted down the middle. He had blue eyes and a bushy, sand-colored beard. They smashed around farm parties and Wichita dance halls, where underage Jeannie carried her head so high no one dared ask for an ID. In a raffle at a party thrown by a Wichita lumber-supply company in 1978, they even won a trip to Paris. Besides the men who left to fight wars, no one in their families had ever been overseas.

As the 1970s drew to a close, discussion in the United States was all about scarcity of resources, both real and perceived. In 1979 came the second oil crisis of the decade, a petroleum shortage related to trade with the Middle East and America's appetite for the world's fossil fuels. Cars lined up for blocks to fill their tanks while gas stations raised their prices, as the global supply-and-demand economy dictated.

People in our corner of society were far removed from the national political discussion. Their eyes were on immediate concerns: Was the hot combine shaking beneath them running right for the wheat harvest? Was there gas in the car to get to work? Had the cattle been fed? Who would pick up children from babysitters?

That's what my early life felt like, and it's how yours would have felt, too—like some invisible hand was making decisions that affected us in ways we didn't have the knowledge to describe or the access to fight.

In July 1979, amid a national panic over fossil-fuel shortages, President Carter visited Kansas City to promote his new energy program. The night before, he had given a televised speech about the oil panic from the Oval Office. Americans were weary and cynical after a couple decades of civil unrest, he said: the assassinations of moral and political leaders, a shameful and bloody war in Vietnam, public revelations about a dirty White House. Carter said the country was experiencing not just an energy crisis but a moral one.

"It's clear that the true problems of our nation are much deeper," he said in his Georgia accent, "deeper than gasoline lines or energy shortages, deeper even than inflation or recession."

The real trouble was with materialism, he said. He had grown up working his family's peanut farm, the sort of experience that doesn't mean you're a good person but does impart lessons about money and resources.

Excerpted from Heartland by Sarah Smarsh. Copyright © 2018 by Sarah Smarsh. Excerpted by permission of Scribner. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

I find that a great part of the information I have was acquired by looking something up and finding something else ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.