Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

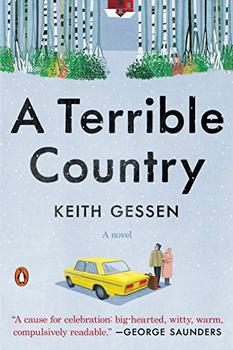

A Novel

by Keith Gessen1.

i move to moscow

In the late summer of 2008, I moved to Moscow to take care of my grandmother. She was about to turn ninety and I hadn't seen her for nearly a decade. My brother, Dima, and I were her only family; her lone daughter, our mother, had died years earlier. Baba Seva lived alone now in her old Moscow apartment. When I called to tell her I was coming, she sounded very happy to hear it, and also a little confused.

My parents and my brother and I left the Soviet Union in 1981. I was six and Dima was sixteen, and that made all the difference. I became an American, whereas Dima remained essentially Russian. As soon as the Soviet Union collapsed, he returned to Moscow to make his fortune. Since then he had made and lost several fortunes; where things stood now I wasn't sure. But one day he Gchatted me to ask if I could come to Moscow and stay with Baba Seva while he went to London for an unspecified period of time.

"Why do you need to go to London?"

"I'll explain when I see you."

"You want me to drop everything and travel halfway across the world and you can't even tell me why?"

There was something petulant that came out of me when dealing with my older brother. I hated it, and couldn't help myself.

Dima said, "If you don't want to come, say so. But I'm not discussing this on Gchat."

"You know," I said, "there's a way to take it off the record. No one will be able to see it."

"Don't be an idiot."

He meant to say that he was involved with some very serious people, who would not so easily be deterred from reading his Gchats. Maybe that was true, maybe it wasn't. With Dima the line between those concepts was always shifting.

As for me, I wasn't really an idiot. But neither was I not an idiot. I had spent four long years of college and then eight much longer years of grad school studying Russian literature and history, drinking beer, and winning the Grad Student Cup hockey tournament (five times!); then I had gone out onto the job market for three straight years, with zero results. By the time Dima wrote me I had exhausted all the available post-graduate fellowships and had signed up to teach online sections in the university's new PMOOC initiative, short for "paid massive online open course," although the "paid" part mostly referred to the students, who really did need to pay, and less to the instructors, who were paid very little. It was definitely not enough to continue living, even very frugally, in New York. In short, on the question of whether I was an idiot, there was evidence on both sides.

Dima writing me when he did was, on the one hand, providential. On the other hand, Dima had a way of getting people involved in undertakings that were not in their best interests. He had once convinced his now former best friend Tom to move to Moscow to open a bakery. Unfortunately, Tom opened his bakery too close to another bakery, and was lucky to leave Moscow with just a dislocated shoulder. Anyway, I proceeded cautiously. I said, "Can I stay at your place?" Back in 1999, after the Russian economic collapse, Dima bought the apartment directly across the landing from my grandmother's, so helping her out from there would be easy.

"I'm subletting it," said Dima. "But you can stay in our bedroom in grandma's place. It's pretty clean."

"I'm thirty-three years old," I said, meaning too old to live with my grandmother.

"You want to rent your own place, be my guest. But it'll have to be pretty close to Grandma's."

Our grandmother lived in the center of Moscow. The rents there were almost as high as Manhattan's. On my PMOOC salary I would be able to rent approximately an armchair.

"Can I use your car?"

"I sold it."

"Dude. How long are you leaving for?"

"I don't know," said Dima. "And I already left."

"Oh," I said. He was already in London. He must have left in a hurry.

Excerpted from A Terrible Country by Keith Gessen. Copyright © 2018 by Keith Gessen. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Censorship, like charity, should begin at home: but unlike charity, it should end there.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.