Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

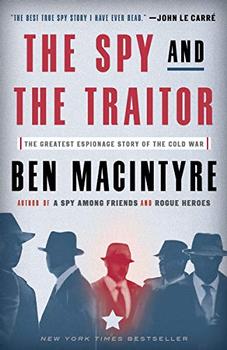

The Greatest Espionage Story of the Cold War

by Ben Macintyre

Oleg Gordievsky emerged from school with a silver medal, head of the Komsomol, a competent, intelligent, athletic, unquestioning, and unremarkable product of the Soviet system. But he had also learned to compartmentalize. In different ways, his father, mother, and grandmother were all people in disguise. The young Gordievsky grew up around secrets.

Stalin died in 1953. Three years later he was denounced, at the 20th Party Congress, by his successor, Nikita Khrushchev. Anton Gordievsky was staggered. The official condemnation of Stalin, his son believed, "went a long way towards destroying the ideological and philosophical foundations of his life." He did not like the way Russia was changing. But his son did.

The "Khrushchev Thaw" was brief and restricted, but it was a period of genuine liberalization that saw the relaxation of censorship and the release of thousands of political prisoners. These were heady times to be young, Russian, and hopeful.

At the age of seventeen, Oleg enrolled at the prestigious Moscow State Institute of International Relations. There, exhilarated by the new atmosphere, he engaged in earnest discussions with his peers about how to bring about "socialism with a human face." He went too far. Some of his mother's nonconformity had seeped into him. One day, he wrote a speech, naïve in its defense of freedom and democracy, concepts he barely understood. He recorded it in the language laboratory, and played it to some fellow students. They were appalled. "You must destroy this at once, Oleg, and never mention these things again." Suddenly fearful, he wondered if one of his classmates had informed the authorities of his "radical" opinions. The KGB had spies inside the institute.

The limits of Khrushchev's reformism were brutally demonstrated in 1956 when the Soviet tanks rolled into Hungary to put down a nationwide uprising against Soviet rule. Despite the all-embracing Soviet censorship and propaganda, news of the crushed rebellion filtered back to Russia. "All warmth disappeared," Oleg recalled of the ensuing clampdown. "An icy wind set in."

The Institute of International Relations was the Soviet Union's most elite university, described by Henry Kissinger as "the Harvard of Russia." Run by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, it was the premier training ground for diplomats, scientists, economists, politicians—and spies. Gordievsky studied history, geography, economics, and international relations, all through the warping prism of Communist ideology. The institute provided instruction in fifty-six languages, more than any other university in the world. Language skills offered one clear pathway into the KGB and the foreign travel that he craved. Already fluent in German, he applied to study English, but the courses were oversubscribed. "Learn Swedish," suggested his older brother, who had already joined the KGB. "It is the doorway to the rest of Scandinavia." Gordievsky took his advice.

The institute library stocked some foreign newspapers and periodicals that, though heavily redacted, offered a glimpse of the wider world. These he began to read, discreetly, for showing overt interest in the West was itself grounds for suspicion. Sometimes at night he would secretly listen to the BBC World Service or the Voice of America, despite the radio-jamming system imposed by Soviet censors, and picked up "the first faint scent of truth."

Like all human beings, in later life Gordievsky tended to see his past through the lens of experience, to imagine that he had always secretly harbored the seeds of insubordination, to believe his fate was somehow hardwired into his character. It was not. As a student, he was a keen Communist, anxious to serve the Soviet state in the KGB, like his father and brother. The Hungarian Uprising had caught his youthful imagination, but he was no revolutionary. "I was still within the system but my feelings of disillusionment were growing." In this he was no different from many of his student contemporaries.

Excerpted from The Spy and the Traitor by Ben Macintyre. Copyright © 2018 by Ben Macintyre. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

It is always darkest just before the day dawneth

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.