Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

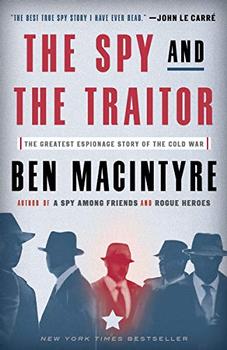

The Greatest Espionage Story of the Cold War

by Ben MacintyreChapter 1

The KGB

Oleg Gordievsky was born into the KGB: shaped by it, loved by it, twisted, damaged, and very nearly destroyed by it. The Soviet spy service was in his heart and in his blood. His father worked for the intelligence service all his life, and wore his KGB uniform every day, including weekends. The Gordievskys lived amid the spy fraternity in a designated apartment block, ate special food reserved for officers, and spent their free time socializing with other spy families. Gordievsky was a child of the KGB.

The KGB—the Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti, or committee of state security—was the most complex and far-reaching intelligence agency ever created. The direct successor of Stalin's spy network, it combined the roles of foreign- and domestic-intelligence gathering, internal security enforcement, and state police. Oppressive, mysterious, and ubiquitous, the KGB penetrated and controlled every aspect of Soviet life. It rooted out internal dissent, guarded the Communist leadership, mounted espionage and counterintelligence operations against enemy powers, and cowed the peoples of the USSR into abject obedience. It recruited agents and planted spies worldwide, gathering, buying, and stealing military, political, and scientific secrets from anywhere and everywhere. At the height of its power, with more than one million officers, agents, and informants, the KGB shaped Soviet society more profoundly than any other institution.

To the West, the initials were a byword for internal terror and external aggression and subversion, shorthand for all the cruelty of a totalitarian regime run by a faceless official mafia. But the KGB was not regarded that way by those who lived under its stern rule. Certainly it inspired fear and obedience, but the KGB was also admired as a Praetorian guard, a bulwark against Western imperialist and capitalist aggression, and the guardian of Communism. Membership in this elite and privileged force was a source of admiration and pride. Those who joined the service did so for life. "There is no such thing as a former KGB man," the former KGB officer Vladimir Putin once said. This was an exclusive club to join—and an impossible one to leave. Entering the ranks of the KGB was an honor and a duty to those with sufficient talent and ambition to do so.

Oleg Gordievsky never seriously contemplated doing anything else.

His father, Anton Lavrentyevich Gordievsky, the son of a railway worker, had been a teacher before the revolution of 1917 transformed him into a dedicated, unquestioning Communist, a rigid enforcer of ideological orthodoxy. "The Party was God," his son later wrote, and the older Gordievsky never wavered in his devotion, even when his faith demanded that he take part in unspeakable crimes. In 1932, he helped enforce the "Sovietization" of Kazakhstan, organizing the expropriation of food from peasants to feed the Soviet armies and cities. Around 1.5 million people perished in the resulting famine. Anton saw state-induced starvation at close quarters. That year, he joined the office of state security, and then the NKVD, the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs, Stalin's secret police and the precursor of the KGB. An officer in the political directorate, he was responsible for political discipline and indoctrination. Anton married Olga Nikolayevna Gornova, a twenty-four-year-old statistician, and the couple moved into a Moscow apartment block reserved for the intelligence elite. A first child, Vasili, was born in 1932. The Gordievskys thrived under Stalin.

When Comrade Stalin announced that the revolution was facing a lethal threat from within, Anton Gordievsky stood ready to help remove the traitors. The Great Purge of 1936 to 1938 saw the wholesale liquidation of "enemies of the state": suspected fifth columnists and hidden Trotskyists, terrorists and saboteurs, counterrevolutionary spies, Party and government officials, peasants, Jews, teachers, generals, members of the intelligentsia, Poles, Red Army soldiers, and many more. Most were entirely innocent. In Stalin's paranoid police state, the safest way to ensure survival was to denounce someone else. "Better that ten innocent people should suffer than one spy get away," said Nikolai Yezhov, chief of the NKVD. "When you chop wood, chips fly." The informers whispered, the torturers and executioners set to work, and the Siberian gulags swelled to bursting. But as in every revolution, the enforcers themselves inevitably became suspect. The NKVD began to investigate and purge itself. At the height of the bloodletting, the Gordievskys" apartment block was raided more than a dozen times in a six-month period. The arrests came at night: the man of the family was led away first, and then the rest.

Excerpted from The Spy and the Traitor by Ben Macintyre. Copyright © 2018 by Ben Macintyre. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.