Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Love and Death in Chicago

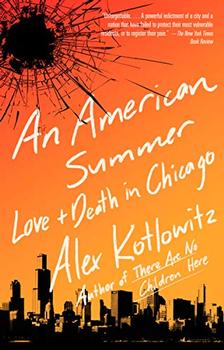

by Alex KotlowitzAn American Summer

Excerpted from Prelude to a Summer

Near midnight on August 19th, 1998, the phone rang, an unusual occurrence at my parents' home in upstate New York where I was visiting with my wife and infant daughter. I got out of bed, and scrambled to the hallway to grab the phone. The voice on the other end sounded familiar but I couldn't quite place it. "It's Anne Chambers," she said. Anne was a Chicago violent crimes detective whom I knew. She told me she was calling from the kitchen in our home in Oak Park, a suburb bordering Chicago. She told me that Pharoah was there with her, and that he may have been involved in a murder. My legs buckled. I sat down to catch my breath.

This was the Pharoah from my book There Are No Children Here, a boy who tread cautiously, who loved school and who was so charming and vulnerable that adults went out of their way to protect him. Shortly after the book came out, Pharoah, who had grown up in one of the city's housing projects, had moved in with me – for what I thought would be a short period. I'd helped get him into Providence St. Mel, a college prep school on the city's west side, and he was struggling, understandably. He couldn't find quiet in his first-floor public housing apartment as rivers of people flowed in and out daily, mostly family and family friends. He called and told me he just wanted to catch up with his school work. Could I be stay with you, for just for a while? he asked. Maybe a week or two? I was single at the time, unencumbered and with a spare bedroom, so I invited him to stay. Though only 12, he knew what he needed. He brought with him a garbage bag filled with clothes – and his school backpack. Those two weeks turned into six years.

When I got married, Pharoah walked my wife Maria down the aisle – along with her dad. We moved to Oak Park as we wanted to be near his school, and we figured it was a community that wouldn't look askance at this unusual arrangement. His adolescent years were rocky. I didn't anticipate how this living situation would pull at his sense of identity. While his mother, LaJoe, supported his decision to live with Maria and me, others in his family didn't. One time, his mother called and after leaving a message forgot to hang up, and so on my answering machine I listened to a five-minute rant by a friend of their family berating LaJoe for letting Pharoah live with a white couple. He don't belong there, the woman told LaJoe. He ain't white.

I knew it had to be hard for Pharoah. He undoubtedly heard these harangues, as well. It's tough enough to be a teen in the best of circumstances, grappling with who you are and who you want to be, and here Pharoah had to figure out who he was while living with two white adults who were not related to him by blood, who were not his parents, who were not even his legal guardians. In particular, he had an older brother – I gave him the pseudonym Terence in the book – who clearly resented Pharoah's decision to live with us, and so he would try to pull Pharoah into his activities in the street. There was also a measure of opportunism here as he knew Pharoah, who had never been in trouble with the law, would not likely draw the attention of the police. It felt like a tug of war, and I often felt on the losing end. At one point, Pharoah knew he had to get away, to find some reprieve from these forces pulling at him, and so at his request we sent him to a boarding school in Indiana, a military academy where he had attended summer camp.

A week after he left, I was tidying up his bedroom, picking clothes off the floor, making his bed and finally cleaning his closet, where on the top shelf I noticed a worn black leather bag the size of a medicine ball. I reached to pull it down. It was bloated with cash. I mean lots of cash. Tens. Twenties. Hundreds. All of it stuffed into the bag without much concern for appearance or organization. I knew right away that it belonged to Terence, that he had probably asked Pharoah to hold it for him. I called a friend, an attorney, for advice. His words were simple: "Get rid of it." He called me back a few minutes later, and clarified, "I don't mean throw it away." So, I called Terence, and told him I had something of his which he needed to retrieve. He refused to come to Oak Park, worried that I'd set him up with the local police so I agreed to meet him on the city's West Side, and there in the middle of a one-way, residential street in the early afternoon, in the open so that we both felt protected, exchanged what turned out to be somewhere in the neighborhood of $18,000. (Terence later accused me of taking $300 from the bag, but that's another story.)

Excerpted from An American Summer by Alex Kotlowitz. Copyright © 2019 by Alex Kotlowitz. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.