Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

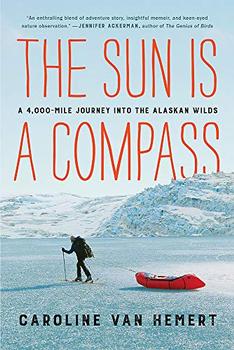

A 4,000-Mile Journey into the Alaskan Wilds

by Caroline Van Hemert

My research focused on a strange cluster of beak deformities that had recently emerged among Alaskan chickadees and other birds. The afflicted birds grew curled and grotesque beaks that resembled something from a dark version of Dr. Seuss. When I began my graduate project, I was sure I could find answers to the mystery of the beak deformities, and that the resulting facts would matter. I fancied myself something of a wildlife detective, searching for clues that would help me crack the case. But instead I quickly learned that the most basic information about the anatomy of a bird's beak was not yet available, and I had no choice but to ask the simplest questions first. I began with the tedious, unglamorous work of slicing beaks into impossibly thin pieces using miniature knives and examining them under high-powered microscopes. I housed chickadees in a laboratory and studied the way their beaks grew, feeling remorse each time I stepped into the room and stared at two dozen pairs of eyes that would never again see birch leaves fluttering in the wind or probe a tree's bark for spiders and beetles.

The tiny black-capped chickadees whose familiar calls belie the fact that they are actually one of the most remarkable species on earth were first my inspiration and then, later, my bane. When my advisor toasted me after my dissertation defense, I cringed, knowing I had failed in the most fundamental of ways. This wasn't a failure in the traditional sense—my calculations stood up to scrutiny, my experiments worked, my chapters were well written. But underneath it all was the ugly fact that I simply didn't care anymore. Between hundreds of hours peering under a microscope and observing chickadees in cages, I had forgotten why I'd wanted to be a biologist in the first place.

During the years of my graduate research, Pat dedicated himself to several building projects and spent more time communing with hammer and saw than with forests or mountains. Since he was a boy, he had been driven to build things. His elaborate childhood forts eventually gave way to cabins and houses, and he had created a fledgling, but successful, design-and-build company. But he was tired of managing budgets, juggling material orders, and shoring up leaky foundations. He questioned why he wasted sunny afternoons buried in drywall dust only to realize that building houses, even those he designed, would never be enough.

In our commitment to education and jobs, we had neglected what mattered most to us. Our calendars were shaped by academic deadlines and construction schedules rather than tide cycles and seasons. We missed the freedom that came with sleeping outdoors for weeks or months at a time. Recently, decisions about whether to have children and how to care for aging parents had started to feel pressing.

My dad had been diagnosed with a degenerative neurological disease. My younger sister was pregnant. The career that awaited me felt increasingly like a sentence rather than an opportunity. Still, I wasn't entirely sure what all of this had to do with our trip or what I hoped to find along the way. I didn't yet understand how traveling across four thousand miles of wilderness would help me face my looming adulthood or a job I wasn't sure I wanted. I didn't realize I needed to find my way back to biology by the same means I had first discovered it.

Only months after we left did I begin to appreciate that this trip offered what ordinary life could not. Clear edges. Truth. Acceptance. An understanding that living with uncertainty is not only OK; it is the only option. Before we started, I wanted nothing to do with the facts that were staring back at me. Life is tenuous. Love is risky. We have so much to lose along the way. I had forgotten the converse side of this equation, that the most precious things in life are those that don't last forever. I needed a crash course outdoors to remind myself that a life is not merely a tally of days, that what really matters cannot be quantified. The glimpse of a wolf 's tawny back, his coat shimmering with dew. The sound of my dad's voice on the satellite phone, holding steady and sure. The look Pat gives me when he knows my pack straps are cutting into my shoulders and my spirit is waning, his expression encouraging me that I can do the impossible.

Excerpted from The Sun Is a Compass by Caroline Van Hemert . Copyright © 2019 by Caroline Van Hemert . Excerpted by permission of Little Brown & Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.