Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

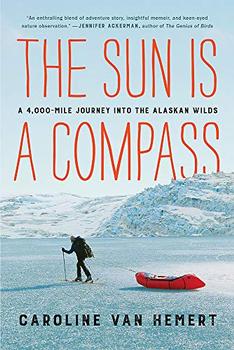

A 4,000-Mile Journey into the Alaskan Wilds

by Caroline Van Hemert

We hadn't originally planned to swim across anything. But now we're perched at the edge of a cold Arctic river without our packrafts; they are on a mail plane heading west. Several days ago, we decided we would shed the extra weight of our boats to lighten our loads. We'll pick them up again in the village of Anaktuvuk Pass, two hundred miles to the west, after much of the steep terrain is behind us. Winter is only weeks away and we need to move quickly if we're to reach Kotzebue before freeze-up. The first season's snow fell last week as we woke to caribou milling around our tent, a small band traveling south. Before we got to the river, our decision to ship the boats seemed like a good one. Now, I'm not so sure.

As we watch the water swirling below, I try to guess how long it might take to swim to the other side, two hundred yards away. Five minutes? Ten? Just as I realize that the distance is equivalent to several laps in a very cold pool, Pat interrupts my calculations by asking where I think we should cross. Before the bend or after? Where the river is widest or narrowest? I see him looking downriver. He is thinking the same thing I am. Where will we end up if we get carried downstream?

We climb down the bank and find a spot to enter, right past a large elbow in the river, and I empty the contents of my pack, searching for the thin waterproof bag that contains my extra clothes. Out comes my sleeping bag, sleeping pad, three stuff sacks of food, satellite phone, rain gear, cooking pot, and camera. When I find the clothes, I begin to undress, goose bumps rising on my skin in the cool air. I re-layer with almost everything I'm carrying—wool long-underwear tops and bottoms, fleece pullover, synthetic vest, nylon pants, and a wool hat—and wiggle into a plastic trash bag with holes cut for my head and arms before pulling on my rain jacket and pants. We know the water will penetrate our layers, but are hoping the rain gear and plastic bag will help to preserve our body heat against the cold. Like an improvised wet suit, Pat explained when he came up with the idea.

I volunteer to go first, not because I'm feeling especially brave, but because one of us must do it. Pat isn't one for chauvinism; still, he hesitates for several moments, staring across the water. He only agrees when I explain that it will be easier for him to rescue me than the reverse. Just in case, I add.

Late last night, curled in our sleeping bags, I tried to envision our crossing. I told Pat that if it seemed too dangerous to swim maybe we could hike back to the nearest village and find someone to give us a ride to the other side. But even as I said this, both of us knew it wouldn't happen. It would mean we had failed.

When we committed to this project—to travel from rainforest to ice-filled sea, from the edge of the continental United States to the edge of the earth—we decided it would be completely on our terms. No roads, no trails, and no motors. We would travel by foot, on skis, in rowboats, rafts, and canoes. We would use only our own muscles to carry us through some of the wildest places left on earth. This wasn't a mandate borne purely of stubbornness, though Pat and I each possess a healthy dose of that trait, but because it would allow us to know the landscape as intimately as we knew each other. Just getting to remote places wasn't the point. We could have hired a plane to drop us off at any number of locations that would qualify as the middle of nowhere. But we wanted something different. We wanted to hear the crunch of lichen beneath our feet, to smell the tundra after a rainstorm, to understand how it felt to walk in a caribou's tracks or paddle alongside a beluga whale.

For years, adventure was simply a part of our lives. It hadn't yet taken on the urgency that arrived, in my early thirties, like a loud and obtrusive neighbor, as my perception of time shifted from lazy and boundless to precious and finite. With it came the understanding that youth is only a temporary pause, a whistle-stop on the train that barrels along, leaving the aging and frail and ill—in the end, all of us—behind. When we first started planning, I had an inkling that this trip would matter more than all of the others we'd taken in our ten years together. Not just because of its scale, which was quickly growing to outrageous proportions, but because if we didn't do it now, we might never have another chance.

Excerpted from The Sun Is a Compass by Caroline Van Hemert . Copyright © 2019 by Caroline Van Hemert . Excerpted by permission of Little Brown & Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.