Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

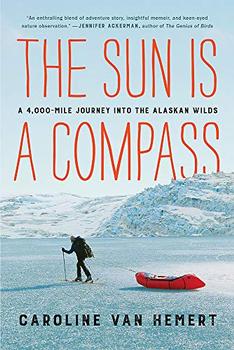

A 4,000-Mile Journey into the Alaskan Wilds

by Caroline Van Hemert

We knew our bodies wouldn't stay strong forever. Inevitably, our responsibilities would grow; our freedom would shrink. I would never again be a thirty-three-year-old on the brink of finishing her Ph.D., childless, disillusioned by the prospect of an academic career, and convinced that whatever it was I needed could be found between two distant places on the map, one a coastal town where I had met my husband, the other a remote, ice-locked land I'd never seen.

I'm shivering before I step into the river. When I begin to wade, the mud soft and forgiving beneath my feet, icy water seeps quickly up my pant legs. My muscles stiffen in response, my knees suddenly wooden, my groin aching. Several steps later I lose contact with the bottom as the current tugs on my hips.

Immediately, I'm being carried downstream, farther from Pat but no closer to the other side. I need to start swimming, and fast. I lace my arms backward through the straps of my pack and attempt to balance my chest on top of the buoyant load as though it is a kickboard. For a moment, this seems to be working. I'm floating and kicking. But my upper body is perched so high above the surface that I can't get any purchase with my flailing legs.

I try again. Lowering my body and leveraging my chin against the bottom of my pack, I kick like hell. I can barely see above the pack, and when I crane my neck, breathing hard, I realize I'm paralleling the shore. I reorient myself and try once more. I flutter my feet but nothing happens. I kick from my hips, but I only move farther downstream. This isn't working. Hurry up.

As I'm floundering, I think of my mom, queen of the breaststroke. Frog kicks? Maybe? After my first contorted attempts, I find a way to use not just my legs but my arms, sliding abbreviated strokes through the shoulder straps. I direct my pack with my chin. It works. I can move and steer and begin to propel myself toward the middle of the channel. Soon, Pat yells from the bluff above that I've made it halfway.

I cheer myself on silently, focusing the only part of my gaze that isn't blocked by my pack onto the trees that are growing larger with each stroke. I can see my progress. Better. Almost there. A surge of confidence follows, and I slow my frantic motions enough to catch my breath. Seconds later, I hit a stiff eddy line. A dozen yards from shore, the swirling water leaves me nearly stationary. Pat shouts something unintelligible. I try to stand up, but a small creek joins the river here and the water is surprisingly deep.

Pat yells again. This time, I hear "Get up!"—but I can't. I'm suddenly afraid. And starting to tire. My inner voice wavers. If you stop now. You. Will. Wash. Away. Act, don't think, Caroline. I force my mind to go still. Robotic. Kick hard. Harder. I try to touch down again, but feel only water beneath my feet.

I close my eyes and channel everything into my legs. Do it. Or else.

After several more attempts, I feel a release. I have finally managed to break through the eddy. As soon as I find contact with the muddy bottom, I wade out of the water and flop onto the shore. I take several breaths lying down, staring up at the sky. When I raise my head and look across the river, I see Pat pump his fist into the air, celebrating for me. I'm only partially relieved. The swim was much worse than I had imagined. Now I have to watch Pat take a turn. He's a strong swimmer, but the river's stronger.

As I stand up and move away from the river's edge, Pat finishes stuffing the last items into his pack. It takes forever. He seals his pack, then opens it up again, retrieving something he left behind on the ground. He arranges and rearranges his load, my anxiety building with each adjustment. When he finally scrambles down the cutbank, he looks small and the river huge.

Within seconds of wading into the water, he's kicking his legs and windmilling his right arm, holding the pack with his left. But I'm not sure his one-armed crawl is working. All but the top of his head is obscured by splashing. Partway across, he switches arms. He slows for a moment and begins to drift downstream. "Come on, Pat," I yell, willing away the excruciating minutes of watching him struggle, and he begins to windmill again. When he's finally near enough for me to see his face, his expression terrifies me.

Excerpted from The Sun Is a Compass by Caroline Van Hemert . Copyright © 2019 by Caroline Van Hemert . Excerpted by permission of Little Brown & Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

We have to abandon the idea that schooling is something restricted to youth...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.