Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

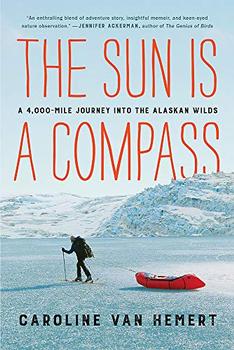

A 4,000-Mile Journey into the Alaskan Wilds

by Caroline Van Hemert

He's wide-eyed and intense. Fighting. Hard.

"Are you OK?" I shout. No response. He hesitates and changes arms. I shout again. Nothing. Fifty yards from shore he's practically at a standstill. I scream that if he doesn't answer me I'm coming in after him.

"Hold on to your pack, I'll be there in a second!" Still no answer. He's moving toward me so slowly he looks stationary. I wade into the water and begin to breaststroke through the eddy, cursing myself for waiting so long. If the current carries Pat much farther, I might not be able to reach him in time.

And even if I do, I'm not sure I can help.

I barely notice the cold this time as I pull against the gray water. Beneath the surface the current churns and grasps. Even without my backpack, it takes all of my energy to fight through the eddy again.

Pat stares intently at the shore and mumbles that he is tired, so tired. Fatigue is only part of the problem. Nearly ten minutes in the frigid river is long enough for hypothermia to set in. When I'm close enough to touch him, I grab his pack and position myself behind him. Without the pack, he can use both of his arms and paddles more smoothly. At the eddy, he glances back at me before stroking hard for shore. I'm right behind him, harnessing the strength that comes with fear. Finally, we stumble out of the water and collapse together on the riverbank.

Horror at what could have just happened replaces the adrenaline coursing through me.

"Damn," Pat says and shakes his head, his eyes shining against the leaden sky. He shivers as he explains that his jacket had filled with water, making it difficult to lift his arm with each stroke. Suddenly, I understand exactly how much I stand to lose. Underlying all of our choices is the fact that if something happened to one of us, the other would have to face the consequences. At times like these, it's impossible not to question whether the risk is worth the reward. Whether we are asking too much of the land, and of ourselves. We stand up, hug each other tightly, and begin to strip off our sodden clothes. Pat jumps up and down to warm himself. I help him with the zippers of his jacket, then work on my own layers.

As I'm wringing out my shirt, contemplating what we're doing here, I hear a sound I've never heard before. I pause, grab Pat's arm, and put my finger to my lips. Listen, I whisper. Silence. And then I hear it again. A familiar chick-a-dee-deedee. But from behind the voice emerges something entirely new. Coarser, more nasal, perhaps an extra scolding tisk at the beginning. The differences are subtle, and I strain to hear each note.

"Oh my god, Pat. I think it's a gray-headed chickadee!"

A moment later, I see not just one bird but an entire family of chickadees flutter onto a nearby spruce tree. Perched on a branch, watching us, are two adults and four fuzzy young.

A gray-headed chickadee is anything but glamorous. As the name describes, it's gray. And small. And very, very hard to find. So hard, in fact, that several teams of researchers and hundreds of hours of surveys devoted to searching its presumed range in northern Alaska yielded only a single data point: one bird. Genetically, gray-headed chickadees are closely related to black-capped chickadees, the commonest of backyard species, which I have also spent half a decade studying. In other ways, they couldn't be more different. Seeing a gray-headed chickadee is special not because its feathers shimmer with iridescence or because it has just arrived from Polynesia but because almost nothing is known about these tiny birds. If I hadn't been paying attention, if I hadn't tuned my ears to the patter of wings and the echo of silence, I would have missed it entirely.

I watch the chickadees as they flit and glean, pulling invisible insects from the needle-clad branches. I take careful note of the shades of gray on the adults' heads and study the contrasting patterns of their feathers, fully aware that I may never see another one of these birds in my lifetime. At the edge of a river that nearly claimed us, I feel the soul-stretching awe that comes with discovery. I feel like a biologist again. Today's rare sighting validates the many latenight computer sessions, the endless hours of packing and planning, every instance of my not feeling smart enough to be a real scientist or strong enough to be a real adventurer. It even makes swimming across the Chandalar River seem like a decent idea. Here, right now, there is only me, Pat, and a family of tiny gray-headed chickadees above us.

Excerpted from The Sun Is a Compass by Caroline Van Hemert . Copyright © 2019 by Caroline Van Hemert . Excerpted by permission of Little Brown & Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Some books are to be tasted, others to be swallowed, and some to be chewed on and digested.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.