Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

The Ship That Changed the World

by Peter Moore1

Acorns

Endeavour's life starts in an unrecorded time, in a subterranean space several inches deep. There, as summer fades into autumn, an oak tree begins life as an acorn.

An acorn is a capsule, protected by a waxy skin. Inside is stored a genetic code and enough nutrients, tannins and essential oils to sustain it during its fragile early weeks. In September, it begins to grow, slowly, until after a fortnight its shell bursts open. For the first time, the acorn's insides can be seen. The ochre hue of the kernel contrasts sharply with the mahogany-brown of the shell, which cracks under the strain. A root dives downward, a tiny probe, seeking water and nutrients. By November, as the earth above gets a coating of frost, the husk of its shell has been pushed clear. In its place are the earliest signs of a stem, which ventures up, seeking light.

After four months the acorn's shell is shattered and discarded and gone. The stem is now the central feature of the tiny plant. It continues to rise. At six months, as the April sun begins to strengthen, it breaks through the soil. It seems other-worldly, blanched, ethereal, like a skeletal arm in a clichéd horror film reaching from the grave. Within days this pallor subsides and a vibrant, joyous green overspreads it. The acorn of the previous autumn is gone. In its place is a seedling oak, an oakling, two inches tall, capped with a pair of helicopter leaves that tilt and turn and thrill to the sun. The plant has no longer to rely on its inbuilt store of energy. Now it photosynthesises in the sunshine, the newest addition to a woodland floor, hidden among brambles, bluebells and wood anemone. More leaves appear and already for those who study it closest they display their familiar, lobed form. As summer progresses these leaves emit a golden glow. Soon the oakling stands out among the flowers, exposed to rabbits, voles, browsing cattle or deer, but otherwise filled with promise for the future.

* * *

No one can say for certain just where the oaks that made Endeavour grew. Thomas Fishburn, the Whitby shipwright in whose yard she was built in 1764, left no records. Perhaps they have been lost or destroyed. Perhaps they did not exist to begin with.

Some might say that the trees grew in the snow-carpeted forests of central Poland. Cut with axes in the bitter continental winter, the timber would be floated down the Vistula to Danzig where it would be sold and loaded into the holds of merchantmen bound for Britain. Plying the old sea paths, those once sailed by the portly cogs of the Hanseatic League, the merchantmen would cross the Baltic, thread through the strait that separates Denmark from Sweden before entering the subdued mass of water called the German Ocean that conducted them to England's eastern shore.

Roger Fisher, a shipwright from Liverpool, voiced a different theory. In 1763 he wrote that the eastern shipbuilding ports of 'North Yarmouth, Hull, Scarborough, Stocton, Whitby, Sunderland, Newcastle, and the North coast of Scotland' sourced their oak chiefly from the fertile lowlands that bordered the rivers Trent and Humber.1 Writing at the moment Endeavour's oak would have been reaching the Whitby yards, Fisher's opinion cannot be discarded. But, equally, it seems more flimsy the more that it is examined. Fisher was a west-coast man. He confessed to having little knowledge of the ways of the eastern ports. All that he had gathered had come second- or third-hand.

Fisher was writing to a different purpose, too. His book on British oak, Heart of Oak: the British Bulwark, was published in 1763, a loaded year in history. This was the year the Treaty of Paris concluded the Seven Years War. During this conflict England's woodlands had suffered violent incursions from foresters, determined to supply the growing navy. Like so many before him, Fisher had been left cold by the destruction. He saw it everywhere. The forests, woods, hursts and chases of Old England were vanishing and he filled his Heart of Oak with evidence of this. Contacts in the timber trade had told him 'fifteen parts out of twenty' of England's woodlands had been 'exhausted within these fifty years'.2 The axe had been thrown indiscriminately. In the river valleys and sunny southern fields, in Wales and the ancient Midland forests, the story was the same.

Excerpted from Endeavour by Peter Moore. Copyright © 2019 by Peter Moore. Excerpted by permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Ordinary Love

by Marie Rutkoski

A riveting story of class, ambition, and bisexuality—one woman risks everything for a second chance at first love.

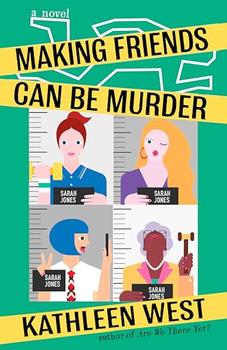

Making Friends Can Be Murder

by Kathleen West

Thirty-year-old Sarah Jones is drawn into a neighborhood murder mystery after befriending a deceptive con artist.

Don't join the book burners. Don't think you are going to conceal faults by concealing evidence that they ever ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.