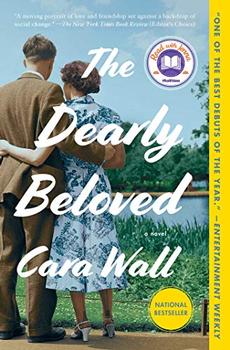

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Because, even though he sometimes wished he could spend his whole life playing baseball, standing in the outfield, tossing lazy balls at the deep green end of summer, when the air stayed warm well after dark, he knew he was very much like his father. Though he loved to feel his cleats kick up dirt, smell the chalk of the baselines, catch a ball in his mitt and throw it back, his body lengthening as the seam slid off his fingertips, he also loved books and everything in them: Latin, physics, algebraic equations and algorithms, the end-stop lines of geometric and philosophical proofs. Though he often longed to lean out over the side of a little boat, bracing his feet on the mast while the wind hurled him forward, pulling the line close to his hip, he also wanted to write papers, debate ideas, use his mind to read closely and accurately, formulate answers to every hidden question.

He enrolled at Harvard and majored in medieval history.

It was there, in late May 1954, that Charles sat in the library reading a book about Catherine of Aragon. He loved the library, its mahogany shelves that climbed to the ceiling, its bounty of lush pages majestically restrained. He loved it especially on days like this, when it was empty, steeped in quiet, electric with promise, as if the books were breathing, alive as big dogs sleeping at the foot of his bed. He reveled in that particular stillness, in which he felt as if he could, at any minute, turn a page and recognize everything there was in the world to know.

His junior year was drawing to a close; as soon as exams were finished, he would set off for another summer on the Vineyard. He was looking forward to vacation. He was ready to be without coat and tie, to sleep late, walk on the beach, and read whatever paperback novels happened to be on hand. It occurred to him that he should take his cousins' children some comic books, carry on his grandfather's tradition, but he realized, with a pang of disappointment, that he did not know where one bought comic books—his had always been hand-me-downs. He marked his page and crossed the long marble room to ask the librarian, Eileen, keeper of the key to the rare manuscripts collection, whether she knew where to buy some.

"Comic books?" she asked, eyebrows raised. "I don't think so." She pushed her chair back and craned her neck to ask the woman in the office behind her. "Marilyn, do you have any idea where to buy comics?" The woman in the office must have shaken her head because Eileen turned to Charles and said, "Apologies."

Charles moved off to the side of the desk, abashed at having bothered a librarian with such a trivial question. But before he went far, he turned back to ask Eileen if she had a phone book. A girl had moved to the front of the tall desk. Eileen was stamping her books, and as she slid the last circulation card into its cardboard holder, she asked the girl, "You don't know where to find comic books in this town, do you?"

The girl looked up, thought for a moment, then said one word: "No."

It was not the flat clap of a mother's angry no; it was not the timid no of someone who wanted to always, and to everybody, say yes. It was a full, round, truthful no—not off-putting, not regretful, just an answer. It perfectly matched the girl who had spoken it. She was tall and straight-standing, wearing a navy blue skirt and a white shirt one might wear to play tennis. Her hair was thick and brown—not a deep, shiny, fashionable brown—just a serviceable, reliable brown, the color of a pony. It was cut in a plain bob. She was slightly tanned and very freckled. She looked exactly like a girl Charles might meet next week at a party on Martha's Vineyard, except that her face was entirely sad.

He didn't think she knew she looked sad. He thought she probably looked in the mirror and saw a well-designed face, with strong cheek-bones, a straight nose, and perfectly fine, rounded pink lips. He thought she probably brushed her hair every morning and thought to herself, Good enough. He acknowledged that there were men in the world who would think she was beautiful and men in the world who would find her plain. He found her both—ravishingly beautiful and exquisitely plain. She was slim and sturdy as a board, lit up with health, and quietly, eternally sad. She looked exactly like a medieval queen.

Excerpted from The Dearly Beloved by Cara Wall. Copyright © 2019 by Cara Wall. Excerpted by permission of Simon & Schuster. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

I like a thin book because it will steady a table...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.