Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

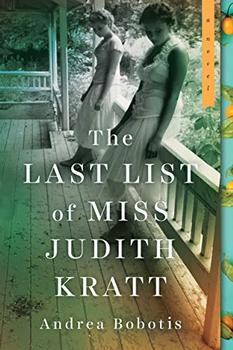

A Novel

by Andrea Bobotis

The depot was one of the places where my brother, Quincy, collected his information. He didn't work for the train company or any of our local businesses, but I guess you could say he was a merchant in his own right, selling the secrets he learned about people. In return, he earned a little money and the racking dread of everyone around him. Never seemed enough, though. I suspect he would have traded it all for a single slap on the back from our father. The railroad inundated us with goods, but for Quincy, recognition was always in short supply. It was a shame. He never did have a head for letters or numbers, but he sure could get a read on people.

I have occasion to think of Quincy frequently these days, as many of the things in this house call out his name. And it is good to remember him, even if it causes discomfort, because don't memories have duties just like everything else in this world?

Here was another question for Olva.

I turned to her and asked, "Aren't memories a little like furniture of the mind?" We were still sitting in the sunroom, watching the late-day sun unburden its remaining light on us.

"Yes, Miss Judith," she replied and left it at that. She was tilting her head back and forth in the way she does, considering a procession of ants ticking along the footboard.

Olva and I share the belief that the world reveals itself to you if you take the time to sit and wait for it. Waiting, I've found, is not most people's area of expertise. Olva is a blessed aberration. Just this morning, she studied a praying mantis for upwards of an hour, admiring the feline strokes of its arms and that long body curved like an ancient sword. As I watched her, it dawned on me that the measured way she tilts her head, combined with the giant spectacles that burden the bridge of her nose, sometimes give her the appearance of a praying mantis. I told her as much, and she seemed to take it as a compliment.

"What I mean," I continued, "is that our memories orient us just like the furniture in this sunroom."

Olva seemed to think about this. "And the view sure is different depending on where you're sitting."

Now, that was not at all what I'd meant. She'd taken my comment a tad literally. A rare slip for Olva, who knows my mind better than anyone. We grew up together, after all. Then it occurred to me that we have never moved any of the furniture in this house. Each piece sits where it did when we were children. It suits me, I suppose, when everything is kept in its proper place.

While I grew attached to the furniture, my brother had his own special relationship with things. Quincy's commodities, you understand, weren't the kind you could touch or lift. They were vaporous, coming to him through hushed voices over fences or eavesdropped conversations, and although they might have remained as innocent as air if left undisturbed, he was a great conjuror, capable of transforming whispers into millstones. Because of this, people pussyfooted around him as if they might bring down the sun if they sneezed.

No one was immune to Quincy's snooping, not even our own mother. We were teenagers when he discovered Mama helping Olva and the other colored folk pick cotton. Quincy promptly alerted the field foreman, a hulking, glandular fellow whose skin, the color of ham, wept sweat even when he wasn't out in the sun.

"Olva," I said, glancing over at her. She had moved on from studying her ants and was sitting there with a gentle gaze. "What was that field foreman's name? The one Quincy sent to reprimand Mama."

Olva's body jerked as if the chair had abruptly withdrawn its comfort. "I can't say I recall," she said.

In fact, I knew his name (Amos something-or-other), but the piece of information was less important to me. I had gotten caught up in the memory. "Quincy was hoping Mama would be punished," I went on. "But when that foreman realized who Mama was and that Daddy Kratt might become embroiled in the conflict, he merely congratulated Mama on how clean her cotton was, which was a polite way of saying she hadn't picked very much for a full day's work. Poor Quincy. He was always trying to claim Daddy Kratt's attention."

Excerpted from The Last List of Miss Judith Kratt Kratt by Andrea Bobotis. © 2019 by Andrea Bobotis. Used with permission of the publisher, Sourcebooks. All rights reserved.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.