Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Discuss | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

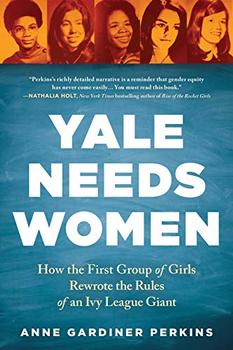

How the First Group of Girls Rewrote the Rules of an Ivy League Giant

by Anne Gardiner Perkins

Brewster made the cover of Newsweek in 1964 and was named by President Lyndon B. Johnson to a U.S. presidential commission the following year and to a second one in 1966. In 1967, the New York Times published a gushing five-page profile of Brewster, and talk began in some corners of a possible cabinet position or even a U.S. presidential run. That same year, Brewster made the cover of Time and chaired a UN policy panel on peacekeeping missions. If Yale men, as some said, were destined for leadership, then Kingman Brewster was striding confidently down the path of his destiny.

Begin with the name: Kingman—or as old friends and colleagues sometimes called him, simply "King," his childhood nickname. For if ever there was a person who embodied the ideal of manhood at Yale, it was Brewster. He was "an imposing figure. Big," said one Yale student, and those who met him were struck by his presence. "Whatever 'it' is, he had it," remarked one Yale trustee. Brewster was handsome by most accounts, with a craggy sort of face and brown hair that was just going gray at the temples. He wore pinstripe suits and shirts handmade in Hong Kong and was descended from ancestors who had come over on the Mayflower—the first trip. He carried with him "the assurance that came from being a direct descendant of the Elder Brewster," explained one of his friends. "You know, 'This is my place.'" And like every Yale president since 1766 but one, Brewster had gone to college at Yale, since, as every Yale man knew, quipped the Harvard Crimson, "a Yale man is the best kind of man to be, and only Yale can produce one."

Yet just when it seemed one might be able to sum Brewster up in a phrase—the patrician leader, the ultimate Yale man, the nation's most well-known university president—a confounding piece of evidence arose to complicate the picture. "He was a very complex man," observed student Kurt Schmoke.

Brewster encompassed a span of seeming contradictions. He was politically conservative but open-minded on many issues. He was both a blue-blood New Englander and a man who sought to learn from others, regardless of their pedigree. He was reserved but sparkled at social gatherings, where he would amuse his friends by mimicking various political personalities or once by singing with gusto an impromptu performance from My Fair Lady. He was forty-nine years old, yet on some of America's hottest issues—Vietnam, race—he stood not with the men of his own generation but with the generation that challenged them.

The students loved him. For their 1968 fundraiser, Yale's student advisory board sold T-shirts printed with the slogan "Next to myself, I like Kingman best." The following year, when Brewster entered a contentious campus-wide meeting on the future of ROTC at Yale, four thousand students rose to give him a standing ovation. On the subject of coeducation, however, Brewster and Yale students stood apart. Indeed, of all the dissonances that defined Kingman Brewster, the contrast between his progressive stances on race, religion, and class and his conservative views on gender was perhaps the most striking.

Brewster refused to frequent clubs that discriminated against blacks or Jews, and the signature change of his administration had been opening Yale's doors to more black students and students from families that could never before have afforded to send their sons to Yale. But when it came to women, Brewster was content with the world as it was. He enjoyed many a meal at clubs that banned women from the main dining room at lunchtime, and as to the idea of ending Yale's 268 years as a men's school by admitting women undergraduates…well, why would anyone want to do that?

By 1968, Yale students had been telling Brewster the answer to that question for more than two years, ever since Lanny Davis became chairman of the Yale Daily News in 1966. "Coeducation should now be beyond argument," Lanny wrote in his debut editorial, which declared that the time was long overdue to end "the unrealistic, artificial, and stifling social environment of an all-male Yale." Lanny did not stop there but proceeded to publish a barrage of pro-coeducation columns and editorials, more than nineteen in all, over the next five months. "Lanny beat the drums day in and day out and, in a wonderfully positive way, harassed the hell out of us," said Brewster's top adviser, Sam Chauncey. And when the Yale Daily News spoke, the men who ran Yale generally listened. The News was one of the oldest and most powerful student organizations on campus. Past chairmen had included Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart, Time magazine founder Henry Luce, and Kingman Brewster himself, who read the Yale Daily News and met regularly with the paper's chairman to get a read on student opinion. When it came to admitting women undergraduates, however, even the News could not convince Brewster that the time for change had come.

Excerpted from Yale Needs Women: How the First Group of Girls Rewrote the Rules of an Ivy League Giant by Anne Gardiner Perkins. © 2019 by Anne Gardiner Perkins. Used with permission of the publisher, Sourcebooks. All rights reserved.

What really knocks me out is a book that, when you're all done reading, you wish the author that wrote it was a ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.