Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

"They want fifty thousand." Blaise spoke in such a rapid nasal voice that Elsie had to ask him to repeat the figure.

"American?" she asked, just to be sure.

She imagined him nodding his egg-shaped head up and down as he answered "Wi."

"Of course, her mother doesn't have it," Blaise said. "These are not rich people. Everyone says we should negotiate. Can maybe get it down to ten. I'm trying to borrow it."

She wished he meant ten dollars, which would have made things easier. Ten dollars and her old friend and rival would be free. Her ex-husband would stop calling her at work. But, of course, he meant ten thousand American dollars.

"Jesus, Marie, Joseph," Elsie mumbled a brief prayer under her breath. "I'm sorry," she told Blaise.

"This is hell." He sounded too calm now. She wasn't surprised by this. Blaise was always subdued by worry. Weeks after he left the konpa band he'd founded and had been the lead singer of, he did nothing but stay home and play his guitar. Then, too, he had been exceedingly calm.

Elsie's former friend Olivia could be appealing. Chestnut colored, with a bushy head of hair that she wore in a gelled bun, Olivia was sort of nice looking. But what Elsie had first noticed about her was her ambition. Olivia was two years younger than Elsie and a lot more outgoing. She liked to touch people either on the arm, back, or shoulder while talking to them, whether they were patients, doctors, nurses, or other nurse's aides. No one seemed to mind. Her touch quickly became not just anticipated or welcomed but yearned for. Olivia was one of the most popular certified nurse's assistants at their North Miami agency. Because of her near-perfect mastery of textbook English, she was often assigned the richest and easiest patients.

Elsie and Olivia met at a one-week refresher course for home attendants, and upon completion of the course they had gravitated toward each other. Whenever possible, they'd asked their agency to assign them the same small group homes, where they cared mostly for bedridden elderly patients. At night when their wards were well medicated and asleep, they'd stay up and gossip in hushed tones, judging and condemning their patients' children and grandchildren, whose images were framed near bottles of medicine on bedside tables but whose voices they rarely heard on the phone and whose faces they hardly ever saw in person.

The next morning, Elsie helped Gaspard change out of his pajamas into the gray sweats he wore during the day. Elsie wished he would let her help him attempt a walk around the manicured grounds of his development or even let her take him for a ride in his wheelchair, but he much preferred to stay at home, in bed. Just as he had every morning for the last few days, he whispered, "Elsie, my flower, I think I'm at the end."

Compared with some mornings, when Gaspard would stop to rest even while gargling, he was relatively stable. His face was swelling up, though, blending his features in a way that made his head look like a baby's.

"Where's Nana?" he asked, using his nickname for his daughter.

Mona was sleeping in her old bedroom, whose walls were covered with posters of no-longer-popular, or long-dead, singers and actors. Elsie knew little about her except that she was living in New York, where she worked for a beauty company, designing labels for soaps, skin creams, and lotions that filled every shelf of every cabinet of each of the three bathrooms in her father's house. Mona was unmarried and had no children and had been a beauty queen at some point, judging from the pictures around the house in which she was wearing sequined gowns and bikinis with sashes across her chest. In one of those pictures, she was Miss Haiti-America, whatever that was.

Gaspard had told her that some years ago, his wife, Mona's mother, had divorced him and moved to Canada, where she had relatives. Gaspard had shared this with her, she suspected, to explain why there was no wife to help take care of him. He would often add, when his daughter showed up on Friday nights and left on Sunday afternoons, that Mona also had to visit her mother on some of the weekends she wasn't with him.

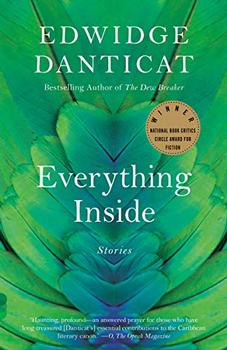

Excerpted from Everything Inside by Edwidge Danticat. Copyright © 2019 by Edwidge Danticat. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.