Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

We heard about people from nearby villages moving to KL or Singapore, or going abroad to Australia or the US, and when they came back they were rich. We were eight, ten, twelve years old – we didn't even know what that meant, didn't know how they got rich or what they did for it, or even how much money you needed to be considered rich. All we knew was that they had left their homes, and now they had more than us. Sometimes they'd come back for Chinese New Year or Cheng Beng and I wouldn't even recognise them, these men and women who'd been part of my childhood. They had big new Japanese cars, Honda Accords, that sort of thing, and all the smaller kids would climb into them. I remember crawling over the seats, rubbing my face on the upholstery and sniffing the newness of it, while another kid pretended to drive the car even though he couldn't even see over the steering wheel. The very presence of such a vehicle in the village made everything else look shabby and poor. The smooth curves of the silvery body were beautiful and effortless and powerful – like a shark cutting through the water. All around it, our houses looked tired. Fragile. Concrete blocks and timber, patched up with zinc sheeting and planks of wood, every element a different colour and texture. If a storm blew through the village at that precise moment, everything else would have been swept away and only the car would have been left standing.

As I grew older and started to learn about the world, I could have asked them what they did in life, what kind of jobs they worked at, how they managed to leave the village and all that, but I never approached them. From a distance I watched them unload presents from the boot, carrying the boxes slowly into their family homes so that the rest of the village could see what they were – a colour TV, a Japanese rice cooker, a hair dryer. It wasn't just their clothes that had changed, but their voices too – not much, just a bit louder and clearer than before, with more English and Mandarin thrown into our dialect. Enough to make me feel that I couldn't communicate with them any more. Or maybe I wasn't that interested. I didn't have to go away and do what they did. I had a belief that life would improve for me, even if I didn't know how.

I wasn't the only one who was optimistic. Around this time, when the new roads and factories were starting to be built, as well as the first of the new suburbs further down south with their shopping malls and car parks, everyone in the village was happy that we didn't have to gut and clean all that fish any more. We were delighted that someone else took our catch from us and cleaned it in a processing plant. Simply hearing that expression made us feel that we were becoming more sophisticated. We knew that we were selling the fish more cheaply than we had before, but it didn't matter. Now we could spend more time at sea. Now we could start farming cockles in the mudflats that stretched out for hundreds of yards right from our front doors. Auntie Hong found a new recipe for prawn crackers that became so famous that day-trippers came up from the city at weekends to buy them, and one day an article appeared in the national newspapers under the title 'Forgotten Seaside Charms'. I can still remember the photo of her, dressed up nicely in a red blouse, with matching lipstick and blue eyeshadow that made her look like a completely different person – who even knew that she had make-up? But there she was, proudly holding a bag of crackers in one hand, and a raw prawn in the palm of the other.

For about ten years, right up until I left the village, we got used to the excitement of the harvests of cockles – the distant sound of the shells as they were emptied from the boats into huge blue plastic tubs for cleaning. A bright sharp drumming noise that you could hear from hundreds of yards away. It was easier than going out to sea for long stretches, men and women could work together, they didn't have to be separated from their families for so long, could see the storms coming and take refuge. The children helped sort through the harvest. We picked out all the empty shells or those already half-open and dead. By the time I left the village, I knew that I would be one of the last of the children to be doing that job. Each year the harvests grew smaller, and we started to find more plastic bags in the mud that got dredged up with the catch, wrapping around the shells and suffocating them. One year I found dozens of condoms too. Maybe a factory had dumped them there, or they were carried downstream in the river – who knows. The younger kids had no idea what they were – they blew them up as though they were balloons, wore them on their fingers and clawed the air pretending to be a Pontianak or some other evil ghost. We laughed a lot that year.

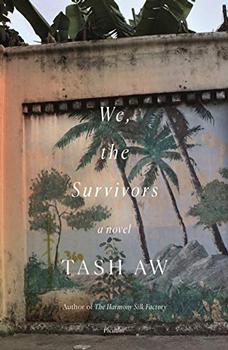

Excerpted from We, the Survivors by Tash Aw. Copyright © 2019 by Tash Aw. Excerpted by permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.