Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Then some of the kids started getting a rash on their hands – red and tender, like the raw flaking patches that follow a burn, except more itchy than painful. I was the only one who guessed that it was from the mud – some of the villagers had the same problem on their feet, from wading in the shallows during the harvest. People started visiting the Monkey God temple to make offerings and prayers. We burnt paper-money – we thought it was our fault, that we hadn't done enough to appease the heavens. Everyone said, If we were richer, we could make more donations to the temple, we'd have better catches. They didn't realise that there was nothing they could do about all the pollution flushing down the river that went right through the cities and emptied into the sea in front of our houses. Or from the offshore prawn farms that had started further up the coast where the water was deeper – you could smell the chemicals sometimes, late in the afternoon when the wind was blowing in the right direction. A sour stink, like old catpiss. Even though I wasn't good at school, I understood that all those big industries further inland which were making cars and air-conditioners and washing machines and American sneakers – they lay close to the same river that washed over our cockle beds, forty, fifty miles away, and they would just carry on emptying their waste into the river, more and more as the years went by. I didn't even feel sad, or angry – why get mad over something you can't change? That was just the way things were.

The only thing that infuriated me was that no one wanted to listen to me when I told them what I thought was happening. Pollution? My grandmother repeated the word as if it was some bizarre other-worldly phenomenon, like an interplanetary collision in another solar system. She turned her back on me and went to the temple. 'Don't know what they teach you in school these days.'

Whenever anyone came back from the temple, they'd talk about destiny. To live like this is our destiny. I never thought about the meaning of fate and chance until I was in prison, and ideas just came to me during those long hours when I was lying on my bed doing nothing. What would have happened if my grandparents had landed further up the coast, or drifted south? If the winds or tides had been stronger or weaker and had carried them to Perak or Johor, or to Port Klang itself? Would I have been a dock worker or a sailor, or maybe a ship's captain? That would have been fun. If they'd landed somewhere else on the coast, where they weren't trapped between river and sea, maybe they'd have travelled inland and gone straight to a city. Maybe then, I would have become you.

I'm just kidding. Of course I couldn't have become you. I know it's not that simple. And I don't mean that I want to become you, or someone like you. It's just that sometimes I can't help thinking about whether I was really destined to be me.

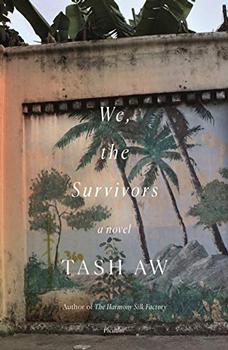

Excerpted from We, the Survivors by Tash Aw. Copyright © 2019 by Tash Aw. Excerpted by permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The low brow and the high brow

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.