Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

I sit and watch the teenagers in school uniforms sharing their fried chicken and showing each other photos on their phones. The boys pretend to be tough, they use the same language I did when I was their age – you know, Cantonese cursing, which sounds really crude and aggressive. If you'd heard me and my friends at that age you'd probably have moved away to the next table. But these kids, they're not like me – they come from the new suburbs close by, they've got decent families. Fourteen, fifteen years old, but they're just babies, relaxing in the mall together after school and playing games on their phones. Even after a whole day at school their uniforms look freshly laundered, not crumpled and grey with sweat – you'd almost say there was starch on their white shirts. Nothing troubles their lives, and in a strange way, their happiness makes me feel innocent again, and hopeful. Those days out in town are special. I have money in my pocket, I feel independent and free, even if it's just for a day or two. That's what those cheques mean to me – a day of freedom. I never pray or even make little idle wishes for them, they just appear. That's how God works, I guess. Always surprising, always giving.

With the injury I suffered in prison I can't work. As you can see, I still have a slight limp, though it's not so noticeable when I'm walking slowly. You only notice it when I have to move quickly, like when I'm running for the bus and just can't shift my leg the way I want to. My brain says, Faster, faster, and for a few seconds I think I can do it, I really think I can get up and sprint for the bus – but my leg just drags. That's when I notice that I'm limping badly, my body sloping from side to side. I also can't pick up heavy loads as I could before. I used to be famous for that. The guys at the factory I worked at when I was a teenager would set me a challenge, see how many crates of fish I could lift at a time, and I'd always surprise them, even though I'm pretty short. It's my stumpy legs that give me balance. People say it's a Hokkien trait, that our ancestors needed short thighs and calves to plant rice or harvest tea and whatever else people did in southern China two hundred years ago, but who cares? All I know is that my legs always served me well, until I got to prison. [Pauses.] It's because of a nerve in my back, something to do with my spine that I don't really understand. The doctors showed me x-rays, but all I could see was the grey-white shapes of my bones. They couldn't correct it without surgery in a private hospital in KL, but who can afford that these days? At the hospital I laughed and said, 'I'm not a cripple, so let's just live with it, OK?' Someone from church suggested I could get a different kind of job, something that didn't involve manual labour, but any kind of job that allows you to sit down in a comfortable office also requires you to have diplomas and certificates and God knows what else these days – and I don't have any. I was never very successful at school.

One time, just a year after I got out of prison, some fellow churchgoers found me a job in their family business, a trading company that imported goods from China and distributed them throughout the country. I had a nice desk, there was air-con in the office, and I didn't have to answer the phone or talk to anyone I didn't know. All I had to do was add up numbers – such an easy job; nothing can be more certain and solid than numbers. I made sure invoices tallied, checked receipts, that sort of thing. Even though I'd never done that kind of work before, I knew about how to manage money. But at that time, I got a bit anxious whenever I encountered anyone new, in a situation that wasn't familiar to me – I guess it must have been my time in prison that did that to me. Nothing serious, you understand, just some hesitations in replying whenever someone spoke to me, lapses between their questions and my answers that made them think I had mental problems. Five, ten seconds – who knows? I watched people's expressions change from confusion, to concern, then irritation. Sometimes frustration, sometimes anger. Some people thought I was doing it on purpose. Once a guy in the office said, Lunseehai, such an arrogant bastard! He shouted it out loud right in front of me without expecting a reply, as if everyone thought the same of me, and that I was deaf and mute and couldn't hear what he was saying. 'Whatever the case,' my boss said after a few months – she was very nice, she understood – 'we think it's better you stop work. Just go home and rest.' Up to that point, I hadn't understood how much I had changed in the previous three years, but losing that job made me appreciate that I had become a different person. Exactly how, I couldn't tell you, but I was no longer the same. I had a couple of interviews for office jobs after that, but nothing worked out.

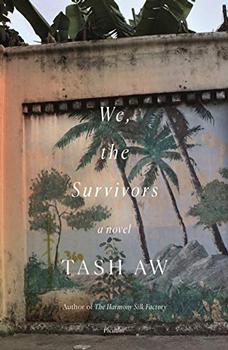

Excerpted from We, the Survivors by Tash Aw. Copyright © 2019 by Tash Aw. Excerpted by permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.