Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

She shrugged. "Sure. Look how old he is."

"He was younger then. They said he was going to be the next Karl Nash."

"Why's he working here, then?"

Clyde shook his head. "What I heard, some little gal broke his heart. That's the way it goes. He's just doing this to get by. He'll find work again when he wants to. Real work."

Max used her to deliver drugs only a few times a week. Pin wished she had a more reliable source of cash. Like Louie, the kid who worked as a sniper, putting up signs around Chicago that advertised new shows at Riverview. He got three dollars a day for that, plus streetcar fare. Or the boys who worked as shills and made twenty-five cents an hour, winning big prizes in fixed carnival games while the rubes looked on. The rubes never won, and they never saw the boys slipping through the back doors of the concessions to return their prizes—child-sized dolls, five-cent John Ruskin cigars, glass tumblers.

And only boys were used to deliver drugs across town. Hashish and marihuana were considered poison, like arsenic. Heroin was worse—Pin had to get it illegally from a druggist on the North Side and bring the glass bottle back to Max, who measured the dope into tiny tinfoil packets, twenty for a quarter. Pin dreaded those trips, especially since two policewomen arrested a druggist on North Clark for selling heroin and cocaine to another delivery boy.

Max had a few regular clients—Lionel, a writer at the movie studio; a woman who performed abortions in Dogville; a Negro horn player who played jazz music at Colosimo's Cafe, a black-and-tan joint, where black people and white people could dance together. The rest were onetime deliveries: students at the university, musicians, whores, vaudeville performers at the theaters along the Golden Mile. Her run to the Essanay Studios was Mondays and Fridays, usually. Lionel made good money, twenty dollars a story, and he pitched three or four scenarios a week.

She knew the work was risky, but it never felt dangerous. If she'd been a fourteen-year-old white girl roaming the South Side or Packingtown, sure. But no one blinked to see a white boy the same age sauntering along the Golden Mile, or ducking in and out of theaters, or Barney Grogan's illegal saloon, hands in his pockets and a smart mouth on him if you looked at him sideways.

She seldom saw Max smoke hashish. Instead she watched in fascination as he applied his makeup. He made a paste from cold cream and talcum powder and used this to cover the left side of his face; then carefully mixed cigarette ash, pulverized charcoal, and dried ink to make kohl and mascara, which he applied with tiny brushes and a blunt pencil to his left eye.

"Why don't you just buy ladies' stuff?" she wondered aloud.

Max laughed. "What do you think they'd say to me in Marshall Field's, I went in and asked for some face paint and rouge?"

"The actors at Essanay use makeup. Charlie Chaplin uses makeup. And Wallace Beery."

"Do I look like Charlie Chaplin?"

After he'd painted his cheeks and lips, he dabbed the edge of one eyelid with adhesive, then affixed a fringe of false lashes made of curled black paper. Last of all, he put on a wig of blond curls. It was only half a wig, like his face was only half a woman's. The right side had Max's own bristly stubble on his chin and neck, a web of broken capillaries across his cheek. Blond hair slicked back so you could see where the orange dye had seeped into his scalp. Outside his tent, a banner depicted an idealized version of the real thing: the She-Male's face split down the middle and body divided lengthwise—natty black suit and shiny shoes, yellow shirtwaist and hobble skirt, the hem hiked up to display a trim ankle.

"Gimme a match," Max ordered. He tapped a cigarette from a box of Helmars, its logo depicting an Egyptian pharaoh. Pin lit the cigarette for him, and he turned away, leaving her to stare at her own face in the mirror, a luxury she didn't have in her own shack. Snub nose and pointed chin, dirt smudged across one cheek, uptilted soot-brown eyes, a chipped front tooth where she'd gotten into a fight. A scrawny boy's face, you'd never think otherwise.

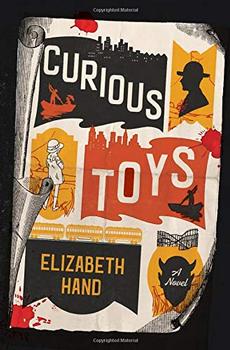

Excerpted from Curious Toys by Elizabeth Hand. Copyright © 2019 by Elizabeth Hand. Excerpted by permission of Mulholland. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Most of us who turn to any subject we love remember some morning or evening hour when...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.