Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Discuss | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

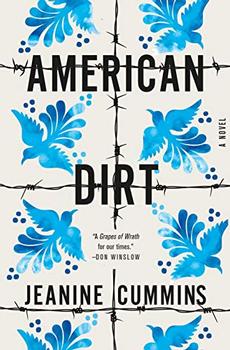

A Novel

by Jeanine Cummins

There must be three of them because Luca can still hear two voices in the yard. On the other side of the shower wall, the third man unzips his pants and empties his bladder into Abuela's toilet. Luca does not breathe. Mami does not breathe. Their eyes are closed, their bodies motionless, even their adrenaline is suspended within the calcified will of their stillness. The man hiccups, flushes, washes his hands. He dries them on Abuela's good yellow towel, the one she puts out only for parties.

They don't move after the man leaves. Even after they hear the squeak and bang, once more, of the kitchen door. They stay there, fixed in their tight knot of arms and legs and knees and chins and clenched eyelids and locked fingers, even after they hear the man join his compatriots outside, after they hear him announce that the house is clear and he's going to eat some chicken now, because there's no excuse for letting good barbecue go to waste, not when there are children starving in Africa. The man is still close enough outside the window that Luca can hear the moist, rubbery smacking sounds his mouth makes with the chicken. Luca concentrates on breathing, in and out, without sound. He tells himself that this is just a bad dream, a terrible dream, but one he's had many times before. He always awakens, heart pounding, and finds himself flooded with relief. It was just a dream. Because these are the modern bogeymen of urban Mexico. Because even parents who take care not to discuss the violence in front of them, to change the radio station when there's news of another shooting, to conceal the worst of their own fears, cannot prevent their children from talking to other children. On the swings, at the fútbol field, in the boys' bathroom at school, the gruesome stories gather and swell. These kids, rich, poor, middle- class, have all seen bodies in the streets. Casual murder. And they know from talking to one another that there's a hierarchy of danger, that some families are at greater risk than others. So although Luca never saw the least scrap of evidence of that risk from his parents, even though they demonstrated their courage impeccably before their son, he knew—he knew this day would come. But that truth does nothing to soften its arrival. It's a long, long while before Luca's mother removes the clamp of her hand from the back of his neck, before she leans back far enough for him to notice that the angle of light falling through the bathroom window has changed.

There's a blessing in the moments after terror and before confirmation. When at last he moves his body, Luca experiences a brief, lurching exhilaration at the very fact of his being alive. For a moment he enjoys the ragged passage of breath through his chest. He places his palms flat to feel the cool press of tiles beneath his skin. Mami collapses against the wall across from him and works her jaw in a way that reveals the dimple in her left cheek. It's weird to see her good church shoes in the shower. Luca touches the cut on his lip. The blood has dried there, but he scratches it with his teeth, and it opens again. He understands that, were this a dream, he would not taste blood.

At length, Mami stands. "Stay here," she instructs him in a whisper. "Don't move until I come back for you. Don't make a sound, you understand?"

Luca lunges for her hand. "Mami, don't go."

"Mijo, I will be right back, okay? You stay here." Mami pries Luca's fingers from her hand. "Don't move," she says again. "Good boy."

Luca finds it easy to obey his mother's directive, not so much because he's an obedient child, but because he doesn't want to see. His whole family out there, in Abuela's backyard. Today is Saturday, April 7, his cousin Yénifer's quinceañera, her fifteenth birthday party. She's wearing a long white dress. Her father and mother are there, Tío Alex and Tía Yemi, and Yénifer's younger brother, Adrián, who, because he already turned nine, likes to say he's a year older than Luca, even though they're really only four months apart.

Excerpted from American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins. Copyright © 2020 by Jeanine Cummins. Excerpted by permission of Flatiron Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.