Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

To the Fahaeans, the rain then, both implausible and prehistoric in that valley where the fields were in love with the river, was a thing largely ignored. That it had once started was already a fable, as too now would become the stopping.

The known world was not so circumscribed then nor knowledge equated with facts. Story was a kind of human binding. I can't explain it any better than that. There was telling everywhere. Because there were fewer sources of where to find out anything, there was more listening. A few did still speak of the rain, stood at gates in a drizzle, looked into the sky, made predictions inexact and individual, as if they were still versed in bird, berry or water language, and for the most part people indulged them, listened as if to a story, nodded, said Is that so? and went away believing not a word, but to pass the story like a human currency to someone else.

The church at that time was not what it is or where it is now. Once Tom Joyce, sacristan, crossed the street in suit and aistcoat, climbed the twenty-seven steps of the belfry to ring what was still an actual bell, a bell blessed by the Bishop and heard in the seven townlands of the parish, people just walked out of their houses and went, the sinners as well as the saints. All routes into the village ran busy with bicycles, horses, carts, tractors and walkers. The roads out the country were not tarred yet, some not even gravelled. The one outside my grandparents' house was mud, tramped hard and soft and hard and soft again, it was foot- and wheel- and hoof-made and bowed upwards in its centre like a spine along which pulsed the townland, passing the open doors, and in that passing picking up and dropping off those pieces of news by which a place is made vital.

And so, for an hour before Mass, there was human traffic of all kinds. You stood outside the door and looked west and what you saw were heads, scarfed, capped or hatted, floating like hosts above the hedgerows. In the fields the cattle, made slow-witted by the rain, lifted their rapt and empty faces, heavy loops of spittle hanging, as though they ate watery light. The human procession, on foot, bicycle and cart, would gradually dwindle – the clack of horseshoes outliving the actual horse by several minutes – but finally it too was swallowed into the green hush. By the time Sam Cregg, whose clock ran slow, in fact and metaphor, passed in the long commandant coat and jodhpurs his brother the General had sent from Burma, the introit would have begun. All roads into the parish fell into an absolute quiet.

Faha then had more to it too than it does now. The shops were small but there were more of them, grocers, butchers, hardware, draper, chemist and undertakers, each implacably marked by the character of their owners. You shopped by blood and tribe. If you were related, however thinly, to Clohessy, or Bourke, who both sold the same tea, flour and sugar, the same three vegetables and tins of imperishable foodstuffs, that's where you did your business. You didn't darken the door of the other. One of the privileges of living in a place forgotten is the preservation of individuality. In Faha, because the centre was distant and largely unknown, eccentric was the norm.

As decreed by mulishness, recalcitrance and tradition, the men gathered before Mass along the two windowsills of Prendergast's post office across from the church gates, with latecomers settling for the sloping one of Gaffney's Chemist. Faha's version of the Praetorian Guard, the men wore suits of brown and grey and hats or caps but no raincoats though the rain would have already saddled their shoulders and made necessary the stratagem of smoking their cigarettes backwards, inside the cup of the hand. They were men from out the townlands whose character was made crystalline by solitude. That they were going to attend church was not in doubt, but because of the thorny relation of religion to the masculine they would show no eagerness and shielded off any sense of the spiritual with a studied casualness and a mastery of the essential art of saying nothing.

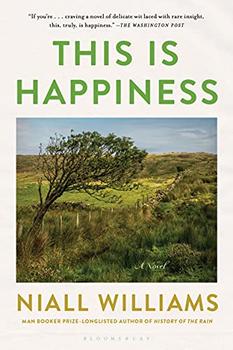

Excerpted from This Is Happiness by Paige Williams. Copyright © 2019 by Paige Williams. Excerpted by permission of Bloomsbury USA. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.