Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

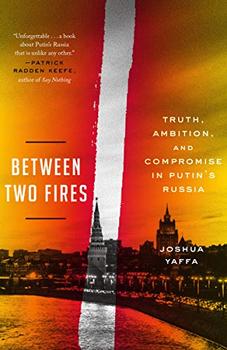

Truth, Ambition, and Compromise in Putin's Russia

by Joshua Yaffa

"I have taken a decision, one which I pondered long and painfully. I am resigning today, the last day of the departing century," Yeltsin began. He spoke with the labored cadence of a tired man. "Russia should enter the new millennium with new politicians, new faces, new people who are intelligent, strong, and energetic," he said. His speech turned reflective, intimate even, spoken in a language of fallibility that Russians had not seen from their leaders before, and have not seen again. "I want to ask your forgiveness—for the dreams that have not come true, and for the things that seemed easy but turned out to be so excruciatingly difficult. I am asking your forgiveness for failing to justify the hopes of those who believed me when I said that we would leap from the gray, stagnating totalitarian past into a bright, prosperous, and civilized future. I believed in that dream, I believed that we would cover the distance in one leap. We didn't," he said. His physiognomy matched his words: his eyes were narrow and tired, his breathing heavy and full of pained effort. "I am leaving now. I have done everything I could."

Yeltsin finished by rubbing a visible tear from his eye. The air in the room was heavy with emotion. Someone from the Channel One crew started to clap, then another, and soon they had all risen to give Yeltsin a standing ovation. They swarmed around him. The most experienced member of the team was a woman named Kaleria Kislova, a veteran producer, then seventy-three, who had filmed every New Year's address going back to Brezhnev. She walked up to Yeltsin, her face ashen and uncertain, and asked him, "Boris Nikolayevich, how can it be?" He gave her a reassuring hug and said, chuckling, "Here it is, babushka, Saint George's Day." It was a moment of wry humor: Saint George's Day, a holiday in late fall, entered Russian lore during serfdom, as the one time each year when an otherwise indentured peasant was free to move from one baron to another. Yeltsin and the Channel One crew drank champagne, toasting the new year and the import of the scene they had all just shared. Ernst was impressed by the gravity of Yeltsin's decision: he had voluntarily given up power, an essentially unprecedented move in Russia's political history—and, in so doing, had restored in Ernst's mind the image of Yeltsin as a decisive and courageous politician. All the equivocating and sloppiness of the past few years seemed instantly swallowed up by this one moment.

The next order of business was for the Channel One crew to film a New Year's address by Putin, which would air at midnight, after Yeltsin's. Putin's face looked young and taut on camera, a picture of vitality compared to the obviously unwell Yeltsin. "The powers of the head of state have been turned over to me today," Putin said. His tone was serious, reassuring, businesslike. "I assure you that there will be no vacuum of power, not for a minute. I promise you that any attempts to act contrary to the Russian law and constitution will be cut short."

Ernst got into a waiting car and set off with copies of both speeches, Yeltsin's and Putin's. He sped from the Borovitsky Gate, a commanding tower of red brick on the Kremlin's western edge, and rode through the capital with a police escort, blue sirens flashing. He headed toward Ostankino, the sprawling complex of television studios and a 2,000-foot-high broadcast tower that beams out the country's main stations, including Channel One. Once he arrived, Ernst handed over the cassettes and, exactly at noon, gave the order to broadcast Yeltsin's address.

Ernst watched from his perch in the channel's control room. Yeltsin hosted a lunch reception with ministers and generals in the Kremlin's presidential quarters. "The chandeliers, the crystal, the windows—everything glittered with a New Year's glow," Yeltsin remembered later. A television was brought in, and his guests, some of the toughest men in the country, watched the announcement in total silence. Putin's then wife, Lyudmila, was at home and hadn't watched Yeltsin's midday address, which meant she was confused when a friend called her five minutes after it ended to congratulate her. She presumed her friend was offering her a standard New Year's greeting—until the friend explained that Lyudmila's husband had become the acting president of Russia. A news segment on Channel One showed Yeltsin and Putin standing side by side in the Kremlin's presidential office, a ceremonial passing of authority more persuasive than any election campaign event. On their way out, Yeltsin told Putin, "Take care of Russia."

Excerpted from Between Two Fires by Joshua Yaffa. Copyright © 2020 by Joshua Yaffa. Copyright © 2020 by Joshua Yaffa. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

To limit the press is to insult a nation; to prohibit reading of certain books is to declare the inhabitants to be ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.