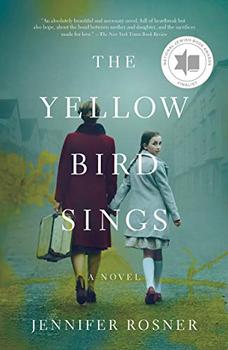

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

by Jennifer Rosner

Henryk enters the barn and begins forking hay out in large piles, blocking the sight line from the neighboring fields and the road.

The farmhouse, white with carved shutters painted a cheery blue, is smaller than the barn and does not fully occlude the view from the road, especially where it curves. The tavern must be somewhere close by because already Róza can hear carousing.

At nightfall Róza shows Shira how to wrap her finger in the clean corner of a rag to make a toothbrush and how to relieve herself in a bucket filled with straw that Henryk will afterward mix with the animals' hay and waste.

Henryk brings a different bucket with food in it. Boiled cabbage and turnips. "Krystyna sent this for you. Just for tonight. She's very frightened."

Róza nods, grateful.

Back beneath hay, Róza presses the heels of her hands to her eyes. Spots of yellow and black bloom there, spreading like spilled dye. They chase away images of Natan and her parents.

Eventually, she opens her eyes to find Shira watching, enchanted, as two rabbits hop sideways on a hay bale and scurry about. If Shira misses her bedtime rituals from home—a drawn bath, warm milk with nutmeg and honey, snuggles from her grandparents—she doesn't show it. On her leg, her fingers tap out the rhythm to some elaborate melody only she hears in her head.

Krystyna enters an hour later, stern and stiff postured, her lips pulled into a straight line. But she's brought more water and a bit of bread. Róza can neither thank Krystyna nor admonish Shira before her girl flits down the loft ladder and, with a dramatic bow, offers Krystyna a small rectangle of woven hay she's made. Krystyna's face softens. Her eyes grow kind. Shira scrambles back to the loft and into Róza's arms.

Chapter 2

Shira practices being invisible. She hunches her shoulders, sucks in her stomach, slinks like a cat. Her mother practices, too, burying herself deep in the hay and beckoning Shira, with a wave of her hand, to settle into her lap and be still. Or with a finger to her lips, she instructs her to stay silent.

The floorboards are rough and the hay is sharp and scratchy. Shira does not understand why they can't go home—why they ever left home—where together her mother and father tucked her into bed as if in a soft, downy nest and where music and the scent of her grandmother's baking wafted through the air.

There, Shira could patter down the hall and join the company, watching as they unclasped the cases of their instruments. Nestled in her grandfather's lap, breathing in his workshop smells of sawdust and lacquer, she bounced and tapped to the ripple of notes from her mama's cello, her tata's violin.

At first, in the tuning and warm-up, everything sounded off-kilter and sad. But then they struck up their songs and the music carried them all, until Shira no longer felt herself settled against her grandfather but in an altogether different place of pure, shared beauty. Vibrant, soulful melodies. Fiery, stomping rhythms. It didn't matter how loud things got—there wasn't a neighbor in the building who didn't relish their playing. Shira could even hum if she wanted to. But here, her mother is insistent: they need to be silent, to hide. So she coils herself tight like a spring and holds herself in.

Shira strives to mute the sound of every movement—her footfalls, her breath. The anticipated stream of her pee, she has learned to mete out in a near-silent trickle. And she knows to cover over and so erase any sign of her existence—a series of vanishing moments—before she retreats beneath piles of hay.

Yet even as Shira wills herself to silence, her body defies her with a sudden sneeze, an involuntary swallow, the loud crack of her hip from being still too long. A calf muscle cramps. An itch needs a scratch. Her bowels press. The most carefully planned movement causes the hay to rustle or a floorboard to whine. Shira looks over at her mother apologetically. Worried, her mother stares back.

Excerpted from The Yellow Bird Sings by Jennifer Rosner. Copyright © 2020 by Jennifer Rosner. Excerpted by permission of Flatiron Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Our wisdom comes from our experience, and our experience comes from our foolishness

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.