Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

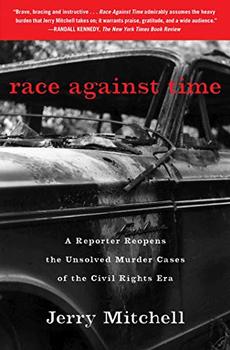

A Reporter Reopens the Unsolved Murder Cases of the Civil Rights Era

by Jerry Mitchell

For forty-four days, the drama unfolded before the nation. Mississippi's US senator Jim Eastland told President Lyndon B. Johnson that he believed the missing trio were part of a "publicity stunt," and Mississippi governor Paul Johnson Jr. suggested they "could be in Cuba." Days before the FBI unearthed their bodies on August 4, 1964, the governor spoke at the Neshoba County Fair, just two miles from that grisly discovery. He told the cheering crowd there were hundreds of people missing in Harlem, and "somebody ought to find them."

The killings came to define what the world thought of Mississippi, and no subsequent events had dislodged it by the time I came here in 1986 as the lowliest of reporters for the Pulitzer Prize–winning newspaper The Clarion-Ledger. I arrived the day before my twenty-seventh birthday, the same day the paper carried a story about the burial of Senator Eastland, the longtime chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee who had bragged about having extra pockets sewn into his jacket to kill all those civil rights bills.

The days of Jim Crow had long passed when I drove into this capital city of nearly 200,000 with my wife and our baby daughter. Jackson was bursting with New South pride and Old South prejudice, but doing its best to conceal the latter. I had been here three years now, from 1986 to 1989, and put thousands of miles on my Honda hatchback in that time, trying to find my feet as a reporter while trying to understand this beautiful and haunted state. When I first heard Mississippians refer to "the War," I thought they were talking about Vietnam—only to discover they meant their great-grandfathers' Civil War, which their descendants, it seemed, had never stopped fighting.

At my desk, I had read the January 9, 1989, issue of Time magazine, which featured the Mississippi Burning movie on the cover. Jackson had been abuzz about the film since last spring, when some residents complained about "Hollywood liberals" invading their town. Disdain turned to curiosity when word spread that actor Gene Hackman had been spotted at Hal and Mal's, a popular pub and eatery. Lunch crowds doubled.

I was curious, too, about this movie and how it would impact Mississippi. I had volunteered to cover its state premiere at a January 10 press screening. At The Clarion-Ledger, the statewide medium-sized newspaper, I felt like little more than a rookie. And tonight's assignment seemed like a welcome break from the court beat, where I faced the daily battle of getting scooped by my more talented rival at the Jackson Daily News, Beverly Pettigrew Kraft. I could hardly count it as a victory that she wasn't in attendance. This was, after all, a minor story.

But I hadn't counted on the attendance of the man sitting next to me at the screening. After the opening scene, his voice startled me, deep and resonant. "That's not accurate," he said, gesturing up at the title card. He leaned over and explained that it was Chaney, not Schwerner, who was the driver that night.

As the night wore on, I learned just how much he knew. His voice blended with the images on-screen. After a young African-American witnessed KKK violence, FBI agents in the film concealed his identity with a cardboard box, driving him around Neshoba County to look for his attackers. The man next to me leaned my way and said, "That really happened."

When the house lights came on, I asked what he thought of the movie.

"It's fiction, all right," the white-haired man replied, explaining that the movie had fictionalized how the FBI had solved the case.

I jotted down his words on a legal pad I was carrying, and I began to chat with the man, who had firsthand knowledge of the case. Roy K. Moore was the retired special agent in charge of the FBI in Mississippi, which investigated the June 21, 1964, killings we had just seen reenacted on-screen. I was grateful he had come, allowing me to tie Hollywood to the real history in tomorrow's newspaper.

Excerpted from Race Against Time by Jerry Mitchell. Copyright © 2020 by Jerry Mitchell. Excerpted by permission of Simon & Schuster. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.