Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

How long they were silent, she didn't know. Three minutes? Twenty seconds? She had her head in her hands.

He placed the soda on the coffee table, sat down carefully at the other end of the sofa. "So, kid," he said at last, "how long are you staying?"

She raised her head. She felt in that moment (how long was she staying? so transparent and cowardly) the value of the two splintered lives, the old Janey who'd stayed behind and the new Janey who'd left, the worth of them switching sides, whooshing by each other, the life she'd catapulted herself into dropping in worth, down, down, plummeting, and the worth of her old life lifting, rising. She felt the vinyl under her (her mother did not and never would own an ugly-ass couch like this), she could smell his old clothes, the cockroaches in the walls, and it was right then (she felt it, like a lock clacking shut) that the deadening began (though it took years), because she didn't pick up her duffel and march back to the station that night, like she knew she should. She stayed right where she was because she was going to make this man know her, or at least pay for not knowing her.

"Great news, Dad," she said. She kicked the duffel at her feet. "Forever!" (Little did she know.)

His expression did not change. He may have flinched a little. He scooched forward, his hand coming up between them—to hug? to smack? to point the way to the door? She leaned in. She was ready for anything. He had something in his hand. Rectangular.

Fate is not determined by one mistake, though they train you to think so, starting with the Bible—one wrong move and you're stuck outside in the rain while the ark floats away without you, or you're wandering the desert for decades. (Janey had gone to a Catholic girls' school until she turned ten and finally triumphed over her mother and went charter.) In fact we have many, many chances to fuck up. And if we figure out how to fix what we fucked, we will fuck it up again.

"Well, that's fine," her father said, his face twitching (was that a smile or a frown? It was the kind of face you really couldn't tell). "Let's just check the scores." He pointed the remote and turned on the TV.

No, it was not her only mistake, but it was certainly her greatest, as others have great loves, great ideas, or great tragedies that befall them. All else Janey could do would pale beside this error. She could kill a man. She could drown herself in a bucket. She could fail to obstruct a politician who would go on to torture millions. Whatever she did going forward would trace back to this, the nadir, the alpha.

She settled back on the sofa, the "scores" flickering across her face. She thought of the old Janey, her other self, the original, who hadn't left, five states away, shimmering in her brownstone in Brooklyn. She could almost see her. That Janey was curled in front of her laptop, working on her Malcolm X paper, and her mother was passing her a bowl of ice cream, because it was that hour. The hour of ice cream.

She lived there with her father for two months and hated every minute of it, but she was too proud to call her mother and say she wanted to go home. She knew they were talking, her mother and "father," trying to figure out the best means to make Janey go back quietly—knew they talked because her mother left her long messages saying they'd talked, and did Janey have any idea how she'd scared her mother, disappearing like that? Did Janey know how lucky she was that she'd made it there without getting kidnapped or crushed under a truck wheel or on the wrong bus to Alaska?

Janey and her father lived like strangers in that apartment, keeping their stuff in bags and eating fast food with ketchup packets in the kitchen. She did try to "connect" a few times. Pulled out her mini–chess set (she was in the club at school), set it up, and asked him if he wanted a game. She instituted an apartment-wide recycling program, plastic and paper in one bag, trash in the other, though she caught him throwing it all into the same dumpster.

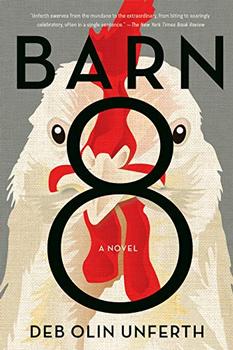

Excerpt from Barn 8. Copyright © 2020 by Deb Olin Unferth. Used with the permission of Graywolf Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota, www.graywolfpress.org.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.