Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

So Janey flew home that day after all, though not in the way she had expected, her father driving her to the airport, murmuring apologies she couldn't hear through the roar, could only see those detested lips move in her peripheral vision. Her father, seeing her through security, handing her some twenties for a cab on the other end, cash that she dropped into the trash in the women's room, not wanting anything from that man. She sat through the wake, the funeral. People placed plates of food in front of her and removed them. People passed into her sight, touched her shoulders, looked earnestly into her eyes and moved their mouths. She was still frozen, had not even begun to thaw when, two weeks later, child protective services turned her around and shipped her right back—to her father. He was her father, after all, and he said he'd take her. She'd been living with him at the time of the accident (that turned out to be the damning fact: she'd been living with him) and she agreed to go, had to, because there was no one else, no other family. Her mother's will had named Janey's grandmother, who was now in a nursing home upstate and Janey saw her twice a year for a day. Other than that there were a few cousins in Mexico whom Janey had never met, and why hadn't her mother ever gone to Mexico and gotten to know them? So she went back, numb and barely speaking. Neither she nor her father seemed to know what to do about school, so she didn't go. She wasn't enrolling in the hick high with the shiny-faced locals unless someone made her. Then a social worker came by and made her. Her father enrolled her as a junior in the local high school.

The first couple of years Janey was so put down by grief and guilt and her sense of no options that she couldn't come out of her numb state without exploding. Her object was to stay as absent as possible, which was plainly like her father. But what else was she supposed to do?

It seemed a bit harsh that for the rest of her life she'd have to pay for one childish mistake she made at age fifteen, the sort of mistake anyone could have made. Surely if she'd been in New York no one would have made her go live with a father she'd never met, who'd never contacted her, never paid support. Surely they would have pawned her off on a friend of her mother's. Other people do stupid things at fifteen and it's no big deal. They have to retake a class, or work winter break to pay for what they broke or stole or crashed, or they have to stay in every weekend for a month, or go to rehab. But her mistake was catastrophic.

It was this understanding, of her mistake, that led her to develop the game, or what was mostly a game. She'd think about the old Janey, the original, and the life with her mother she would be leading—the one where she hadn't left and therefore her mother hadn't been in the car that day (theoretically) and therefore was still alive, and everything had stayed the same between them and around them. What would the old Janey, the original, the real one, be doing right now?

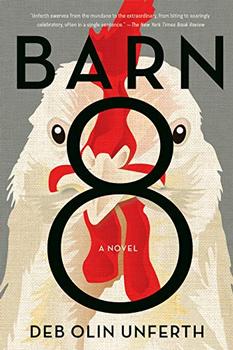

Excerpt from Barn 8. Copyright © 2020 by Deb Olin Unferth. Used with the permission of Graywolf Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota, www.graywolfpress.org.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.