Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

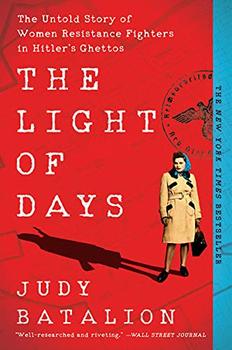

The Untold Story of Women Resistance Fighters in Hitler's Ghettos

by Judy Batalion

A coin from the early twelve hundreds, on display at the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw, shows Hebrew letters. Already, Yiddish-speaking Jews were a large minority, integral to Poland's economy, working as bankers, bakers, and bailiffs. Early Poland was a republic, its constitution ratified around the same time as America's. Royal power was curtailed by a parliament elected by the small noble class. Jewish communities and nobles had mutual arrangements: the gentry protected the Jews who settled in their towns and gave them autonomy and religious freedom; in turn, Jews paid high taxes and carried out economic activities forbidden for Christian Poles, such as loaning and borrowing capital at interest.

The 1573 Warsaw Confederation was the first document in Europe to legally mandate religious tolerance. But as much as Jews were officially integrated into Polish culture and shared philosophies, folklore, and styles of dress, food, and music, they also felt different, threatened. Many Poles resented Jews' economic freedom. Jews subleased whole towns from nobles, and Polish serfs begrudged the rule of their Jewish landlords. The Catholic Church disseminated the hateful and absurd falsehood that Jews murdered Christians—especially babies—in order to use their blood for religious rituals. This led to attacks on Jews, with occasional periods of wide-scale riots and murder. The Jewish community became close-knit, seeking strength in its customs. A "push-pull" relationship existed between Jews and Poles, their cultures developing in relation to the other. Take, for instance, the braided challah: the soft, egg-rich bread and holy symbol of the Jewish Sabbath. This loaf is also a Polish chalka and a Ukrainian kalach—it's impossible to know which version came first. The traditions developed simultaneously, societies tangled, joined under a (bitter)sweet gloss.

In the late seventeen hundreds, however, Poland broke down. Its government was unstable, and the country was simultaneously invaded by Germany, Austria, and Russia, then divided into three parts—each one ruled by a captor that imposed its own customs. Poles remained united by a nationalist longing, and maintained their language and literature. Polish Jews changed under their occupiers: the German ones learned the Saxon language and developed into an educated middle class, while the Austrian-ruled (Galician) Jews suffered from terrible poverty. The majority of Jews came to be governed by Russia, an empire that forced economic and religious decrees on the largely working-class population. The borders shifted, too. For example, Jędrzejów first belonged to Galicia; then Russia took it over. Jews felt on edge—in particular, financially, as changing laws affected their livelihoods.

During World War I, Poland's three occupiers battled each other on home ground. Despite hundreds of thousands of lost lives and a decimated economy, Poland was victorious: the Second Republic was established. United Poland needed to rebuild both its cities and its identity. The political landscape was bifurcated, the long-honed nationalist longing expressed in contradictory ways. On the one side were nostalgic monarchists who called for reestablishing the pluralistic Poland of old: Poland as a state of nations. (Four in ten citizens of the new country were minorities.) The other side, however, envisioned Poland as a nation-state—an ethnic nation. A nationalistic movement that advocated for purebred Polishness grew quickly. This party's entire platform was concerned with slandering Polish Jews, who were blamed for the country's poverty and political problems. Poland had never recovered from World War I or its subsequent conflicts with its neighbors; Jews were accused of siding with the enemy. This right-wing party promoted a new Polish identity that was specifically defined as "not the Jew." Generations of residency, not to mention formal equal rights, made no difference. As espoused by Nazi racial theory, which this party adopted giddily, a Jew could never be a Pole.

Excerpted from The Light of Days by Judy Batalion. Copyright © 2020 by Judy Batalion. Excerpted by permission of William Morrow. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.