Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

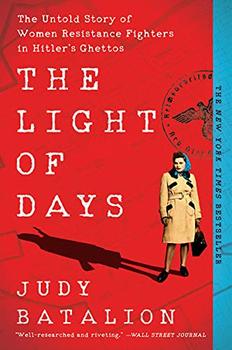

The Untold Story of Women Resistance Fighters in Hitler's Ghettos

by Judy Batalion

The central government instituted a Sunday-Rest law and discriminated against Jews in public employment policies, but its leadership was unstable. Just a few years later, in a 1926 coup d'état, Poland was taken over by Józef Piłsudski, an unusual mix of monarchist and socialist. The former general and statesman championed a multiethnic land, and although he did not particularly help the Jews, they felt safer under his semiauthoritarian rule than under representative government.

Piłsudski, however, had many opponents, and when he died in 1935, as Renia turned eleven, the right-wing nationalists easily assumed control. Their government opposed direct violence and pogroms (which occured anyway), but boycotts of Jewish businesses were encouraged. The Church condemned Nazi racism but promoted anti-Jewish sentiment. At universities, Polish students championed Hitler's racial ideology. Ethnic quotas were enforced, and Jewish students were corralled into "bench ghettos" at the back of the lecture hall. Ironically, Jews had the most traditionally Polish education of any group, many speaking Polish (some exclusively) and reading Jewish newspapers in Polish.

Even the small town of Jędrzejów saw increasing antisemitism through the 1930s, from racial slurs to boycotting businesses, smashing storefronts, and instigating brawls. Renia spent many evenings staring out her window, on guard, fearing that anti-Jewish hooligans might burn down their house and harm her parents, for whom she always felt responsible.

The famous Yiddish comedy duo Dzigan and Schumacher, who had their own cabaret company in Warsaw, began to probe antisemitism on stage. In their eerily prescient humor sketch "The Last Jew in Poland," they portrayed a country suddenly missing its Jews, panicking about its decimated economy and culture. Despite growing intolerance, or perhaps inspired by their discomfort and hope, Jews experienced a golden era of creativity in literature, poetry, theater, philosophy, social action, religious study, and education—all of it enjoyed by the Kukielka family.

Poland's Jewish community was represented by a multitude of political opinions; each had its own response to this xenophobic crisis. The Zionists had lost patience feeling like second-class citizens and Renia frequently heard her father speak of the need to move to a Jewish homeland where Jews could develop as a people, not bound by class or religion. Led by charismatic intellectuals who championed the Hebrew language, the Zionists disagreed fundamentally with the other parties. The religious party, devoted to Poland, advocated for less discrimination and that Jews be treated like any other citizen. Many Communists supported assimilation, as did many in the upper classes. With time, the largest party was the Bund, a working-class, socialist group that promoted Jewish culture. Bundists were the most optimistic, hoping that Poles would sober up and see that antisemitism wouldn't solve the country's problems. The diasporic Bund insisted that Poland was the Jews' home, and they should stay exactly where they were, continue to speak Yiddish, and demand their rightful place. The Bund organized self-defense units, intent on staying put. "Where we live, that's our country." Po-lin.

Fight or flight. Always the question.

* * *

As Renia matured into early adolescence, it's likely that she accompanied her older sister, Sarah, to youth group activities. Born in 1915, Sarah was nine years older than Renia, and one of her heroes. Sarah, with her piercing eyes and delicate lips that always hinted at a smile, was the omniscient intellectual, the savvy do-gooder whose authority Renia simply felt. One can imagine the sisters, walking side by side at a clipped pace, all duty and energy, both donning the modern fashion of the day: berets, fitted blazers, shin-length pleated skirts, and short cut hair pulled back in neat clips. Renia, a fashionista, would have been put together from head to toe, a standard she upheld her entire life. The interwar style in Poland, influenced by women's emancipation and by Paris fashions, saw the replacement of jewels, lace, and feathers with a focus on simple cuts and comfort. Makeup was bold, with dark eye shadow and bright-red lipstick, and hairdos and skirts were shortened. ("One could see the entire shoe!" wrote a satirist at the time.) A photo of Sarah in the 1930s shows her wearing low, thick-heeled pumps that allowed her to march—a necessity because women in this era were constant walkers, traveling long distances to work and school by foot. No doubt heads turned when the sisters entered the meeting room.

Excerpted from The Light of Days by Judy Batalion. Copyright © 2020 by Judy Batalion. Excerpted by permission of William Morrow. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.