Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Excerpt

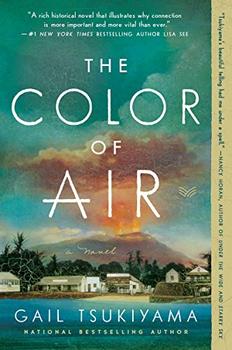

The Color Of Air

Nori hurried back from the green bungalow to the Okawa Fish Market, across the road from Hilo Bay. One of the two- story clapboard buildings on Kamehameha Avenue, it had formerly been the Hilo Town Bar. She passed the older, two- story S. Hata Building, and the S. H. Kress & Company Building, where all the wealthy haole ladies, whose husbands managed the plantations and ran the banks, came down from their big houses up the hill to have lunch and shop for the latest fashions. The buildings gleamed in their Art Deco newness, both products of the sugar wealth in Hilo town during the past forty years that had kept the town growing, and dimmed all the small family- owned businesses of her childhood. Nori swallowed her rising anxiousness and pushed through the crowded streets. She didn't want to be late to Daniel's party.

Since the stock market crash six years ago, there had been other changes. The once- quiet downtown streets were noisy and restless, teeming with agitated Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, and Portuguese men waiting desperately for work on the docks. Nori heard that thousands of Filipino workers had already been sent back to the Philippines by the plantation owners, but it was hard to tell as she slipped by so many sour, unwashed bodies, avoiding eye contact as she picked up her pace and clutched her basket close.

"Lady! Lady," someone called out to her, but she kept moving.

In the past few months there'd been countless drunken fights, a stabbing down on the docks outside of Hoku's Bar, and the window of Ching's Laundry had been smashed by a brick in the middle of the night. Nori remembered a time when it never crossed her mind to lock the market's door after dark. Closed meant closed. Now things were different.

Still, as Hilo town continued to grow around her, the one thing that hadn't changed for three generations was the Okawa Fish Market. Every morning, varieties of succulent tuna and snapper, moonfish and swordfish had been caught and brought in, still thrashing, by the Okawa fishermen, first by her father- in- law, and her husband, Samuel, and then, as soon as they graduated from high school, her sons Wilson and Mano. Even now, when Nori stepped into the cool, dark market, the heavy sea salt fish pineapple mildew odor sent her right back to the first day its doors opened twenty- five years ago.

Nori had married Samuel Okawa right after they graduated from high school in 1904. They were both seventeen, and she became pregnant with Wilson almost immediately after they moved into his family's house close to the wharf, staying in Samuel's boyhood room. He began working full- time with his father as a fisherman, while she helped his mother at the family fish stand. Nori worried about Samuel going out to sea, taking the boat out in rough waters, confronting unexpected storms or unforeseen injuries. She nourished her courage with old deities and all the fishing lore passed down through generations, but her heart raced with every month's full moon, which carried another meaning: the currents would be rough in the morning. Unrelenting, unpredictable, unforgiving, the sea was governed by Kanaloa, the god of the ocean. Samuel lived by reading the weather signs, watching the currents and the cloud formations, a language Nori learned to decipher during her first year of marriage. It was a skill that was as suffocating and illuminating as it was frightening and life- saving.

Six years later she opened the fish market. Nori had just turned twenty- three in 1910 when she urged her husband's family to expand the simple lean- to that sold the freshest fish in Hilo down by the wharf into a larger market. Samuel and her in- laws resisted. "We're fishermen, why make more trouble, eh?" her husband had argued. Nori simply smiled and remained insistent. She'd given him two sons in the past five years, and was ready for something more than just changing diapers and waiting for her husband to return home each day bringing the rank smells of fish and sweat. No matter how much her husband protested, she knew he would eventually relent. Samuel was a good, hardworking man, whom she'd known and trusted since he was a boy sitting next to her at Queen Lili'uokalani High School, but Nori had all the business acumen in the family. Hadn't she been the one to put away enough money to buy the building and start the market in the first place?

Excerpt from The Color of Air by Gail Tsukiyama . Published by HarperVia. Copyright © 2020 HarperCollins.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.