Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

The Education of a Monster

A Disgraceful Episode

AS I WRITE THESE words, it occurs to me that I have never known a tale to be so beyond belief as that which I am about to relate to you, dear girl. Yet nothing I have written has ever been so true. Paradox, all is paradox. Perhaps I have taken leave of my senses once and for all. You see, as a youth, I contracted the pox, no doubt from Jeanne Duval. This scourge is known, in old age, to drive its victims to madness, so that they know not the difference between the real and the unreal. I live in the permanent shadow of my impending lunacy. But as you will learn, it is not the only way in which Jeanne haunts me still. Indeed, if I am writing to you at all, it is because of Jeanne.

We are not strangers, you and I. I am the gentleman you met this afternoon in the Church of Saint-Loup, accompanied by Madame Édmonde. Your name is Mathilde. You are a sullen, bovine sixteen-year-old girl. Despite the assurances of the nuns who discharged you into Madame Édmonde's care, you can barely read. Admittedly, you recognize the letters of the alphabet, but that can hardly be called reading. You can scribble your name, but that can hardly be called writing. Still, I trust that Madame Édmonde knows what she is doing. I have no choice.

As you know, I am a poet. I am forty-three years old, though I appear much older, due to many years of deprivation. Success, at least of the worldly variety, has hitherto eluded me, despite the excellence of my verse. In April last year, in poor health and low spirits, I left Paris, where I had lived almost all my life, determined to see out the rest of my days in Brussels as an exile. I had somehow convinced myself that I had better prospects here. I was following in the footsteps of my publisher and dear friend Auguste Poulet-Malassis, who had left Paris hoping to make some money by publishing pornography—the Belgian censor is less prudish than his French counterpart—and smuggling it into France. I arrived filled with an élan I had not known since my youth.

Upon my arrival, I rented a room in an old, decrepit hotel called the Grand Miroir on the sole basis that I liked its strange and poetic name. It had little else to recommend it. I asked for the cheapest room. It was on the uppermost floor, up three flights of a tortuously winding staircase. There was a small bed with a mattress of old damp straw, a tattered divan, a rickety writing desk, a stove that emitted more smoke than heat, and a chest of drawers. I was, at least, able to observe through a solitary window the clouds drifting across the sky, above the cityscape of rooftops and chimneys. It was one of my few remaining consolations. As long as I have a glimpse of sky, I can tolerate almost any hardship.

I had hoped my self-imposed exile would bring an end to the daily humiliations of my Parisian existence. In fact, my prospects in Brussels were no better than anywhere else. I was soon beset by the same trials and tribulations that had dogged me before: cold, damp, penury, sickness, and calumny. I have been unable to keep up with my expenses and the only reason the proprietors, Monsieur and Madame Lepage, have allowed me to remain is the hope that, should I die, they might be paid their due out of my estate—with interest, of course. They not only hope for my death, they are counting on its imminence.

* * *

The evening on which this tale begins, early last month—that month being March of 1865—I had just dined at Madame Hugo's. Madame Hugo has always been unfailingly kind to me despite my occasional fits of distemper. Like me, her husband is in exile, but he lives in comfort in Guernsey with his mistress, playing the part of the national hero.

His wife shares a large bourgeois house on Rue de l'Astronomie with her son and his family. A little colony of Parisians has formed in Brussels lately, despite its backwardness. We have taken flight from Napoleon's grand-nephew and his overzealous prelates. As Auguste was also invited to dine at Madame Hugo's, he met me at the hotel and we walked there together, as we had many times before, arm in arm in case one of us should trip on the paving stones—the streets here are in a lamentable condition. As we walked, complaining about Belgium as we habitually did, I felt the wetness of the paving stones ooze into my shoes through holes that had opened up in the soles, which for lack of money I had not had repaired. As we neared the Hugo residence, Auguste urged me to guard against my usual outbursts of slander and to preserve my honor, and his too, which was linked to mine by friendship.

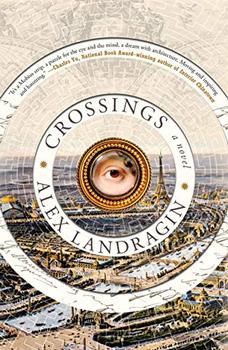

Excerpted from Crossings by Alex Landragin. Copyright © 2020 by Alex Landragin. Excerpted by permission of St. Martin's Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are always so certain of themselves, and wiser people ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.